A new exhibition by writer/artist/publisher/technologist James Bridle, "The Glomar Response," is on view through September 5, 2015 at NOME, Berlin. Here, Bridle discusses the exhibition with Fiona Shipwright.

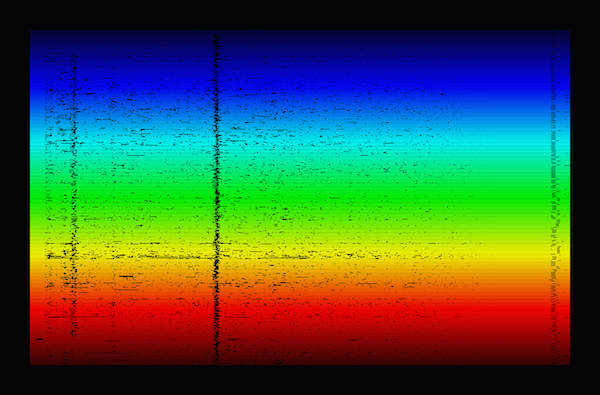

James Bridle, Fraunhofer Lines 001 (Committee Study of the Central Intelligence Agency's Detention and Interrogation Program) (2015). Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de

The title of the show is "The Glomar Response"—the official term for the response that one can "neither confirm nor deny" a particular fact. What do you find compelling about this term?

What I find so extraordinary about the Glomar Response is its spread. The fact that this thing—which was developed by the CIA at the height of the Cold War to disguise a top-secret operation to retrieve nuclear misses from the bottom of the ocean—is now a standard part of the vernacular of your local council. But it's also interesting because within that response is this kind of deep ambiguity of these knowledge forms; there's the danger of overloading the visible/invisible idea, the notion that "I've made this all transparent and possible for you to understand," because that assumes that it is even possible to do.

That is the underlying basis for these kind of technological forms of knowledge, this kind of data ontology. It's the same principle that surveillance relies on, the idea that "we'll just keep on gathering information, then we'll know for sure," that some absurd level of truth can be reached. At that point the Glomar Response actually almost feels like a kind of honest response to the genuine complexity of the world, that's now undeniable. Or rather it should be undeniable but we keep trying to generate these simplistic stories out of it.

This exhibition is structured around technological investigation, specifically this weird knife-edge between how technology obscures but also reveals—once you have literacy to read it. That balance is something I am constantly fascinated by. The work in in the show is also about limits; whether it's the limits of transparency, the limits of investigation through technological methods, the limits of visualization as means of representing data in a useful way, or the limit of what you can know from data alone, which is kind of the thing that I really want to get into understanding and critiquing.

"Unseen" can just be another word for "overly complex." There's also the question of what form of "unseen" is it? Is it unseen because it's quite literally invisible or is it because it's something that takes on the texture of the rest of the world? Or is it because it's just so deeply embedded into these technologies? Whilst I like the very literal "artness" of throwing paint over the invisible man, making something visible is also just bringing criticality to bear on these things, isolating them and discussing in such a way that means we can actually have a conversation about them.

James Bridle, Seamless Transitions (2015). Animation by Picture Plane. Commissioned by The Photographers’ Gallery, London.

For Seamless Transitions you used freely available archival material to create architectural visualisations of the "unphotographable" spaces of the UK's immigration detention and deportation apparatus, but they arguably tell far more than any static photographs could. Are we past the point where a "no photos" rule is enough to keep something out of sight?

The subject matter of the Seamless Transitions piece is not even at the highest level of concealment. If I wanted to do the same thing and create visualizations for installations on Diego Garcia [a US military base and one of the geographical subjects of the Waterboarded Documents series, which features water-damaged evidence relating to a CIA black site that may have been used for waterboarding], whilst it would certainly not be impossible because there are satellite images, there wouldn't necessarily be things like the actual architectural floor plans available.

James Bridle, Diego Garcia (Waterboarded Documents 001) (2015). Photo by Bresadola+Freese/drama-berlin.de.

But what that makes clear is that the limits to what we can see now are not determined where you can physically get to yourself: it's largely determined by what you're interested in. The thing that's stopping us seeing this stuff is a lack of interest. You can see every point on the earth's surface in Google maps but it still requires someone—either by chance or with a particular interest—to come along and say, "I need this bit" and to make sense of it.

Now you can see everything, what do you want to see? Or conversely, if it's all there, then why haven't we seen this? A lot of my projects are about filling in an image gap where one exists because that usually points to some kind of process of occlusion.

There's one work associated with the show which we don't see displayed: Citizen Ex, a browser extension that maps one's "Algorithmic Citizenship"—how you appear to the internet as a collection of data and the "real" consequences of that. The word "citizenship" often has connotations of democracy and participation, but in your project it has a more ambivalent status. Can you talk more about this?

I am uncomfortable with that aspect of Citizen Ex, for many reasons. I don't want to enact citizenship online. I don't think we should base new forms of identity on the nation state—the project is an articulation of one idea, and whilst it's not the one I necessarily want to see in the world it is a reflection of the way things are being constructed today.

When the question is asked, "why is surveillance is bad?" one of the reasons is because of the limitations it puts on individual expression—and there's no more obvious example of that than how the early net functioned. It allowed one to experiment with one's presentation of self, and that's just being stamped out on the larger platforms where people now operate. Preventing surveillance in the corporate context prevents advertising, targeting and money; that which is necessary for capitalism to function online. And that's the image that we've increasingly built the web in.

Berlin-based writer Fiona Shipwright is an editor of uncube magazine. She can be found on Twitter @edwardiansnow.