Former Ministry of Highways Building, Tbilisi.

There is a sense in which all architecture is authoritarian, regardless of its ideals. No matter how many community meetings a planning process incorporates, in the end only one building may be built; one architecture, which by its very existence precludes another. The eventual users and non-users of the space may make minor modifications. They may open or close windows, but in the end they must deal with the consequences of the building, whether it is a postwar housing project or a San Jose strip mall. They must negotiate its little manipulations, and have little in the way of recourse if these should become oppressive.

Artists, at least of a particular bent, are not the sort to take authority at its word. Even under the most oppressive of conditions artists find ways to critique and to criticize, and to present alternate theories of the world. They respond to all forms of power, architecture included, through gestures that range from the most basic act of graffiti to Ai Weiwei's "studies of perspective."

In Ministry of Highways, a volume edited by Joanna Warsza, artists take on the systems and aesthetics of architecture, and question the very existence of walls, even those that tower above them. The collection centers around the Georgian Ministry of Highways building in Tbilisi, and the temporary art show "Frozen Moments: Architecture Speaks Back" that was held in the building in 2010, before renovations were completed and the building was occupied by its new owner, the privately owned Bank of Georgia.

The building is a stunning, cantilevered form, little-known in the West at the time of its construction in 1975, though it eventually made the cover of publications like Domus and even Time Magazine as an example of Soviet space age idealism. It has its roots in Constructivism, Brutalism, and Modernism, but its designers George Chakhava and Zurab Jalaghania found their unifying theory in a concept called Space City. In the introductory text of Ministry of Highways, Chakhava describes the idea:

Contemplating the laws of the nature, I formulated this solution: As we know forests cover most of the earth. A forest consists of different trees, which have crowns separated from the earth, connected by tall communicating trunks to the roots. Between the earth and the crowns—columns—there are a lot of free spaces for other sentient beings to create a harmonious, balanced world with the forest.

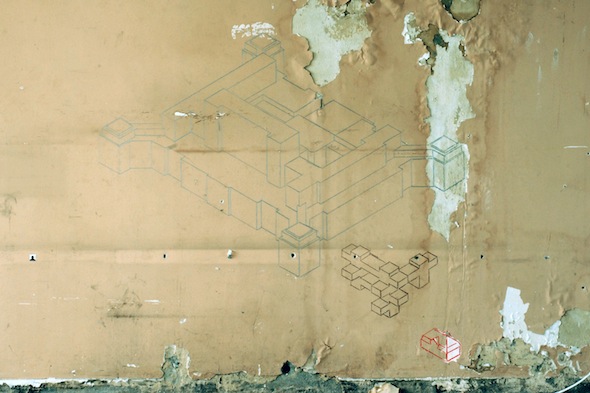

Such a natural metaphor might seem unlikely for a massive concrete structure. But such dialectics are the unspoken theme of the "Frozen Moments" show. For his piece Frozen Scales, artist Josef Dabernig took CAD data from the original design of the building, and drew them on the decaying interior walls of the building. Aleksandra Wasilkowska's Creeping Utopia created an infrastructure of PVC water pipes on the roof, for the purpose of watering the weeds that had come to grow on the building's facade. Rather than create the structure herself, Wasilkowska hired laborers and gave them only very general specifications, allowing them to choose the exact layout of the haphazard plumbing system. The collective Urban Research Lab's Post-Soviet Transformations looked at architecture in Tbilisi from a more holistic perspective, documenting a number of social housing shifts in the city's micro-districts, and looking at how decentralized patterns were replacing the previous influence of the Soviet Union. And in Agnieszka Kurant's Flying Ministry, the realist/idealist dialectic finds its performative climax, as a small model of the Ministry building is flown from the roof, attached to a mass of white balloons.

Above: Josef Dabernig, Frozen Scales (2010). Below: Aleksandra Wasilkowska, Creeping Utopia (2010), photographed during the opening of "Frozen Moments: Architecture Speaks Back."

Ministry of Highways includes supplemental text and essays that describe the breakdown of infrastructure in post-Soviet satellite states: in Tbilisi's frozen, decaying cable car system, and in the Baku public beach, immediately adjacent to oil rigs just off shore. These are joined by essays about the ad hoc means for dealing with such crises: so-called "Kamikaze Loggias," additional rooms commonly built out from second floors on stilts to deal with housing shortages; and a "Guide to Social Networks in the Soviet Microrayons," detailing ways for coping with scarcity while building community in the small micro-districts of Tbilisi. And in between these stories of crisis and intervention are those of utopia as well, such as Yona Friedman's drawings about forming communicating communities, and Aleksandra Wasilkowska's essay "Don't Panic, Organise!" about the success of bottom-up organization and how it contributed to her work in the show. These dialectics, between massive structure and individual and collective performative intervention, build as a critical perspective throughout the text.

But while the book forms a beautiful statement about the artist’s ability to construct creative interventions within architectural and infrastructural crises, it also remains under the shadow of the spreading structure of the building itself, which had already been purchased by the Bank of Georgia at the time of "Frozen Moments." While the temporary site was evocative and inspiring as a space of perceived possibility amid the ruins of a fallen empire, that possibility had already been foreclosed upon by the rise of global capitalism. The building was refurbished; in the typical pattern of capitalist renewal, the new tenants wiped away all traces of the past, painting over the work and dismantling the installations. The book remains a resource full of interesting ideas, and the artists' projects have relocated to less regulated spaces, to tenement stairways and kamikaze loggias. Decentralized interventions remain sporadic and temporary, idealisms remain as ideas, and hegemonic structures, both architectural and social, remain hegemonic structures.

Interior, Bank of Georgia headquarters (formerly Ministry of Highways building), Tbilisi.

The question remains: what is the utility of commenting on something so intractable as architecture, and the infrastructure that surrounds it?

Perhaps one would expect too much of art in asking it to permanently shift architecture and infrastructure. Art is not expected to ultimately be didactic. Even when artists create functioning tools, they do so in order to propose or enact an idea. Beyond "Frozen Moments," works like Philipp Ronnenberg's Open Positioning System or Julian Oliver's Border Bumping create awareness of the power structures at play in GPS and cell phone towers, respectively. But at the end of the day, Ronnenberg's seismic positioning system and Oliver's revised national maps are only small suggestions, footnotes in the larger narrative of infrastructural hegemony. Clara Boj and Diego Diaz's Observatorio, and Ricardo Dominguez and Brett Stalbaum's Transborder Immigrant Tool were both conceived of as tools—the first to help residents of Tallinn, Estonia visualize the WiFi geography of the city, the second to help migrants cross the US-Mexico border safety. But even if both of these technologies actually work and work well, how can these small tools affect the larger structures of electromagnetic space, and immigration politics? The impetus in this art is to do something—but what is really being done?

It is not any of these artists' sole responsibility to change the terrain of architecture and infrastructure. It is the responsibility of all of us to do so—and those who uphold the hegemony of architecture are the ones whose actions we should be interrogating most. Asking the contributors to Ministry of Highways why their creations are now only held within the flat pages of a book is a small question. The larger question, which the art implies, would be to ask the Bank of Georgia why there are no artists working in their cantilevered halls today.

Ad hoc, community-focused, bottom-up, technological interventions do not tend to result in massive pours of concrete or any other lasting edifice. The concrete is poured, and the people respond. While an artist may take equal inspiration from Kamikaze Loggias and the Ministry of Highways building, there is a reason that such structures look different, and will forever exist in different places. There is a reason that celebrity architects are hired to build impressive office buildings, and that artists are sometimes allowed to play in the wreckage of outdated fashions.

Kamikaze Loggia, Tbilisi 2007, Photo: Levan Asabashvili/Urban Reactor.

This is the way that things are. We create art as if our paint could open up a gap in the wall for an ideal space, as perfect as we imagine it, not in the real terms of bricks and mortar. When we write our graffiti on the wall of the massive edifice of our contemporary power structures, we must use words that are of the futile nature of graffiti. This paint will be removed and the wall will remain. We write on the wall because it is there, and because there are only walls, and this is the only architecture we have managed to snatch from the ever-present eye of the cop and the camera. To interfere with steel is to be architectural, but to only paint the walls with criticism, is to be artistic. We are artists because we are not architects; we question the built environment because we are not designing it. In a virtual "safe mode," we build ideas rather than more walls. Our creation of only ideas in the face of hegemonic systems is our hollow material, in which we stand waist-deep, as it rises towards our throats.