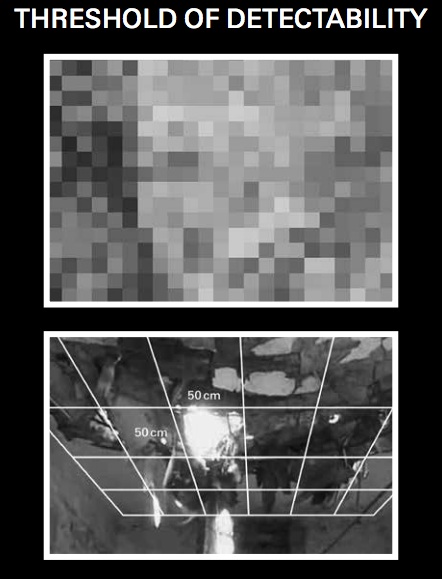

“Threshhold of Detectibility” Top: the roof of a building in Miranshah, Pakistan, that has been hit by a drone-fired missile. the form of destruction is masked in the photo’s pixelation. Source: Digitalglobe, inc., March 31, 2012 Bottom: Still from footage broadcast on MSNBC of the aftermath of a March 30, 2012 drone strike in miranshah, pakistan, showing the entry hole of a missile through the ceiling of a room. Visualization: Forensic Architecture. Page from Forensis program.

Any act of looking or being looked at is mediated by technology. This is true of any scientific process too, where each tool or method of looking is developed with a purpose in mind which influences the data that it produces. This is precisely what forensic investigation reveals: not only the reality of an event, but also the intention of a viewing mechanism and the political weight of that intention once made visible. Representations of warfare illustrate this as successfully as any art object.

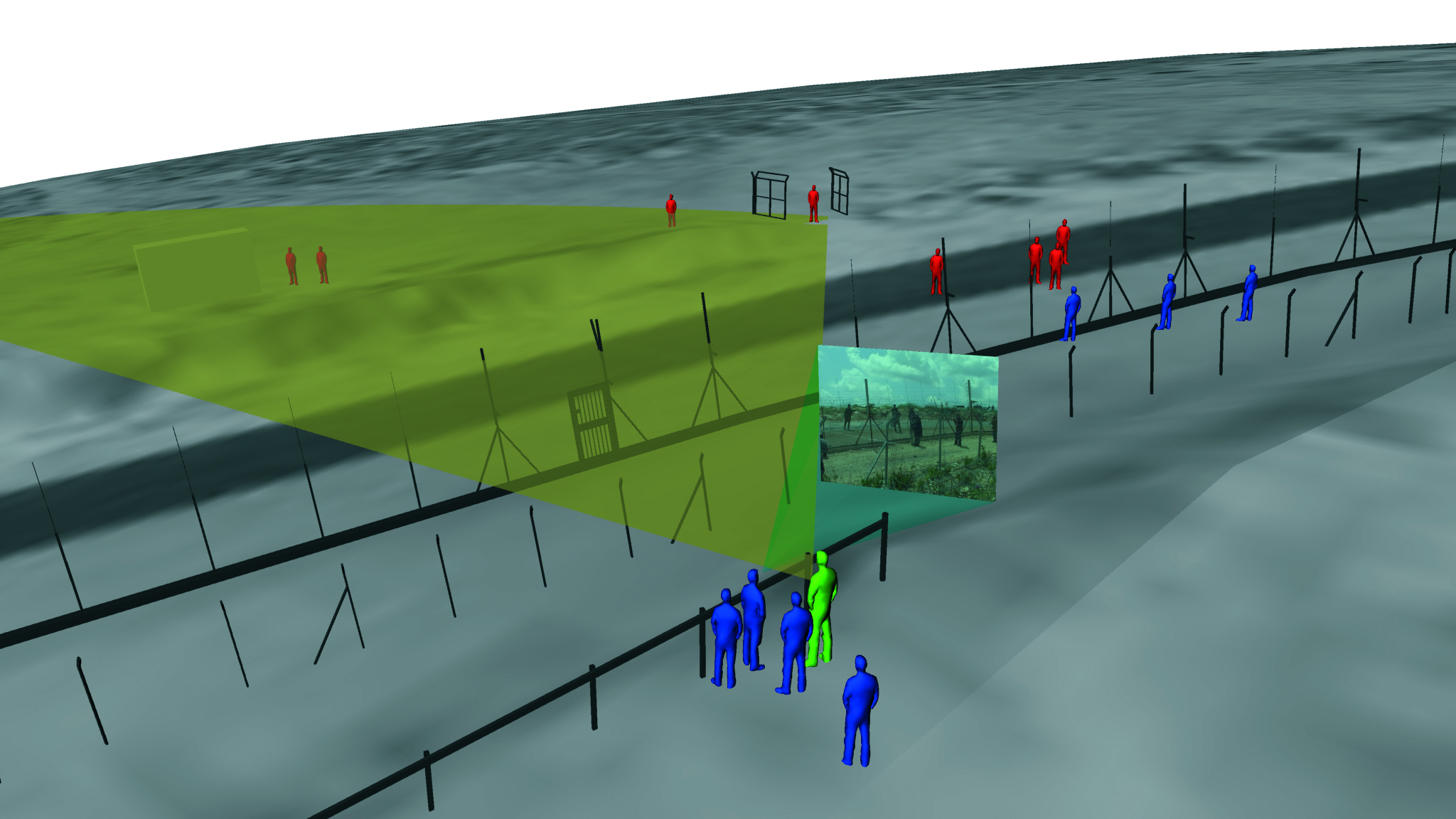

As part of the exhibition Forensis, now on view at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, Forensic Architecture and SITU Research investigate drone strikes in situations where state-mandated degradation and pixelation of publicly available surveillance footage is a legal regulation rather than a visual constraint, and drones are designed to evade the digital image. Missiles are developed that burrow through targeted buildings, leaving holes that are smaller than a low resolution pixel. Attacking at "the threshold of visibility," the legal, political, and technical conditions equally attempt to remain invisible. The job of forensics is then to recover them.

Yet to what extent is an exhibition able to bring these conditions into visibility? The Forensis exhibition, curated by Anselm Franke and Eyal Weizman, investigates the forums in which spatial and material evidence is recorded and presented. Exhibiting aesthetic and political practices by individuals and independent organizations (mostly centred around the Forensic Architecture project at the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London), the exhibition raises the political questions that are inherent within changing techniques of media representation across government, surveillance, and law, while also making sure to self-reflexively embed its own apparatus of representation within its critical framework.

Mostly staged in the one main exhibition room of HKW (below the Anthropocene Observatory and its energetic programme of talks, films and performances), Forensis includes a wide survey of different forensic presentations—involving imaging processes, satellite images, 3D visualizations, models and videos—which have, in their real lives, been mobilised as evidence on behalf of prosecution teams, civil society organizations, activists, human rights groups, and the United Nations. While the Roman forum, the etymological root of the word "forensics," was a site of bustle, noise, and vigorous market trading, the site of contemporary forensics is represented here through a series of projects that require vigorous cognitive processing. Within the exhibition, the viewer is encouraged to drift between a datafarm of text, video essays, and computer renderings, all of which provide the architecture through which we understand choice examples of photographic evidence. However, for such an information-heavy viewing experience, the exhibition also reflects strongly on the aesthetic and performative dimensions within the process of forensic research.

Image from the 3D virtual model reconstruction of the scene at the moment of the shooting of Bassem Abu Rahma. © Forensic Architecture and Situ Studio

The Roman forum, as Franke and Weizman point out in the exhibition text, was a "multi-dimensional space of negotiation and truth-finding in which humans and objects participated together in politics, law and the economy." The development of forensics in the second part of the twentieth century marked a departure from these origins, as juridical practice shifted away from a sympathy toward the human witness (we're reminded of the importance of testaments in the trial of Adolf Eichmann in illustration of this) and toward a renewed faith in objective analysis. However skulls don't have smiles, and forensic findings can nonetheless be inconclusive—they often produce neither stable nor fixed alternatives to human uncertainty and ambiguity. Forensis is careful to argue for a technological realm in which humans and objects meet each other halfway, and this is one of its charms. Several projects remind us not to lose sight of the human subject within the forensic process. In one exhibit, images of a barricade in the Paris Commune before and after a police attack are compared—an early example of the role of photography in negotiating history. However, no record of the people present is captured in the first image, as they were moving too fast for the shutter speed. This serves as compelling reminder of the need not to erase the human body in our engagement with these technologies. "Can the Sun Lie?" a documentary-style film by Susan Schuppli, examines the conflicting authority of an indigenous storytelling tradition versus scientific expertise. As the film narrates, "in the Canadian arctic the sun is setting many kilometres further west along the horizon, and the stars are no longer where they should be"—observations made by indigenous populations, yet deemed unverifiable and thus illegitimate by scientific communities. This is post-production occurring before an image is even captured; representation is a continually recurring process, with no real sense of "before" or "after." The truth, as such, needs to be conferred.

Here is the political kernel of the exhibition: if interpretation of information is a continually occurring process, then it is one we need to maintain an active relationship to, which means understanding the constructedness of any truth-situation, but also taking opportunities to reconstruct truth. Illuminated within an area of the exhibition on predictive forensics, "pre-emptive targeted assassinations" by drone-fired missiles dispense punishment not for crimes their targets have committed in the past but for attacks they will presumably commit in the future. Thus, contemporary security management uses statistical prediction to replace documented action as the basis of enforcement and philosophical concepts such as free will are determined in the name of security. Understanding how forms of control navigate through the legal system offers opportunities to consider the validity of other possible futures outside of the lens of accumulated data, granting individuals the ability to question the ethics of preventative measures based on statistical prediction. The materiality and aesthetics of the seemingly objective is emphasized throughout the exhibition.

“Decoding video testimony”. Animating the shadows allowed FA to establish the time of the day in which a video capturing the ruins of a market targeted in Miranshah, North Waziristan on March 30th 2012 was shot as well as the form of the ruin. © Forensic Architecture

This is one of the strengths of Forensis, its willingness to wear its ideology on its sleeve and not shy away from making political claims, in contrast with the ambiguity of many contemporary exhibitions. Within Forensis, the form of the exhibition functions primarily as a forum for sharing research and its methodological interpretations, and not as a platform for exhibiting individual works or the identity of the makers of the work. The exhibition argues that forensics is a political practice primarily at the point of interpretation. Yet if the exhibition is its own kind of forensic practice, then it is the point of the viewer's engagement where the exhibition becomes significant. The underlying argument in Forensis is that the object of forensics should be as much the looker and the act of looking as the looked-upon. Perhaps this critical framework can extend beyond the scientific and juridical spheres, and influence our understanding of epistemology and the politics of looking in the world at large.