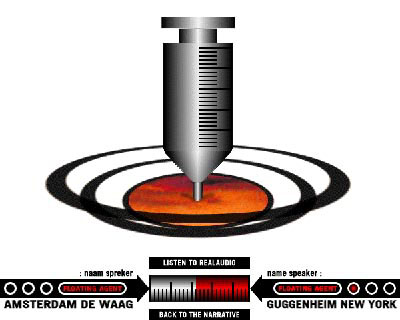

Shu Lea Cheang, Brandon, Bigdoll interface,

Shu Lea Cheang, Brandon, Bigdoll interface,

collaboration with Jordy Jones and Cherise Fong, 1998

In 1998, the Guggenheim Museum launched its first web-based art commission, Shu Lea Cheang's Brandon. Over the course of a year, the collaborative, dynamic piece would look at the complexity of gender, sexuality, and identity through the life and death of Brandon Teena/Teena Brandon, a Nebraska youth who was raped and murdered after his biological sex as a woman came to light in 1993.

Oft-cited in new media art history as one of the first widely recognized pieces of net art, the Brandon site has been offline for the last year or so; the Guggenheim plans to restore the work in the very near future.

Cheang now resides and works in Paris. I spoke to her about Brandon, 14 years after its launch:

YH: How did you first come to conceptualize Brandon? What were the circumstances for its commission?

SLC: Brandon was conceived at a time that I moved from actual space to cyber/virtual, claiming myself a cyber-nomad. It was around the mid-90s, and there was high hope for a super-highway, for a virtual world where race/gender does not matter any more. (I think it was the ad copy of MCI communications?). Meanwhile, two articles came out at Village Voice, one about Brandon Teena's rape/murder case by Donna Minkowitz and the other Julian Dibbell's A Rape in Cyberspace. I had been experimenting with boundary crossing between the actual (state/nation) and virtual (anonymous/avatars), which needed to take up a durational performative format.

By 1995, I wrote out a proposal which was to be a one-year web narrative project following my feature film Fresh Kill (1994). At the time, I guess it was unusual to conceive a durational web work, to be unfolded by episodes, by staged virtual performance 'events' supported by actual space installation. At the time, David Ross was the director of the Whitney Museum. He had the vision to expand the museum into cyberspace. Curator John Hanhardt (who has exhibited three of my major works: color schemes (a solo show in 1990), Those Fluttering Objects of Desire (1993, Whitney Biennial), and Fresh Kill (1995, Whitney Biennial)) took up the curation of Brandon. By 1998, Hanhardt had moved to the Guggenheim Museum and took Brandon with him. At the Guggenheim, Matthew Drutt, Associate Curator for Research, helped realize the curatorial admist the Guggenheim's venture into the virtual museum with Asymptote Architects.

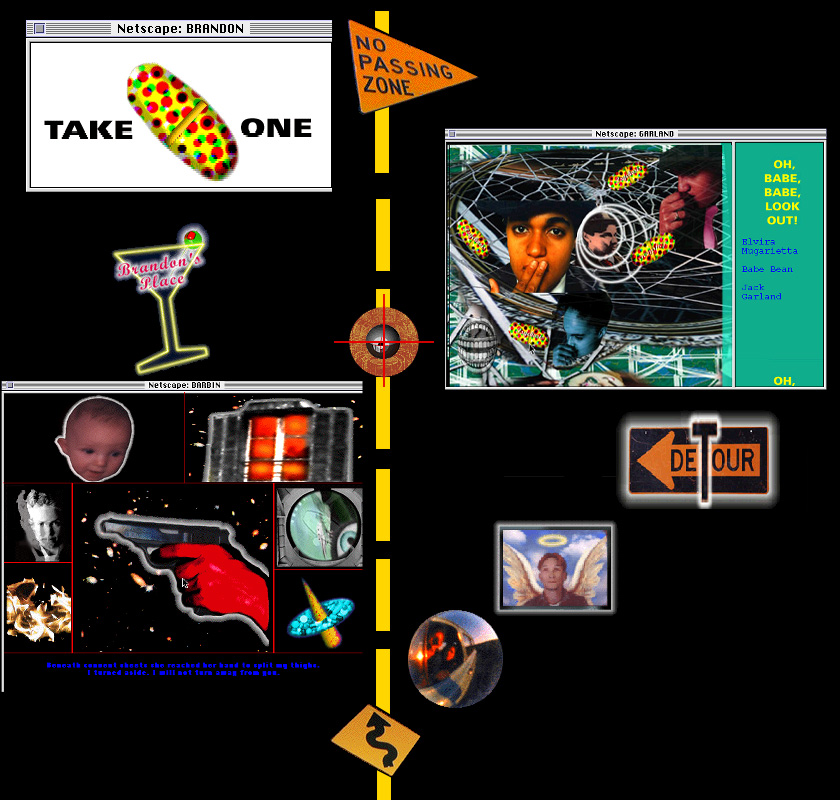

Brandon, Roadtrip interface,

collaboration with Jordy Jones, Susan Stryker, and Cherise Fong

![]()

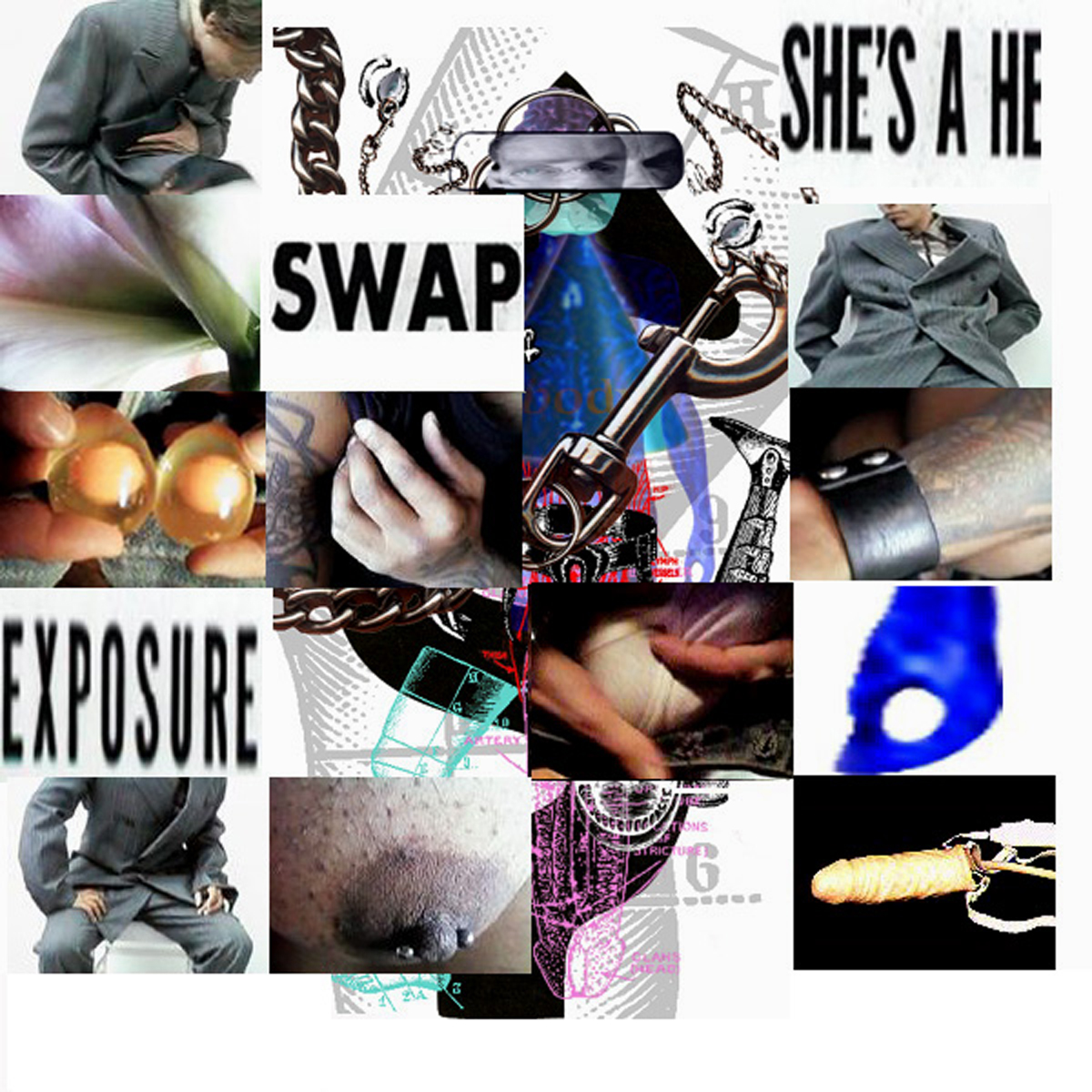

Brandon, Panopticon interface,

collaboration with Auriea Harvey and Beth Stryker

How were you thinking of interfaces? Did your work in film and other medium inform how you work in digital form?

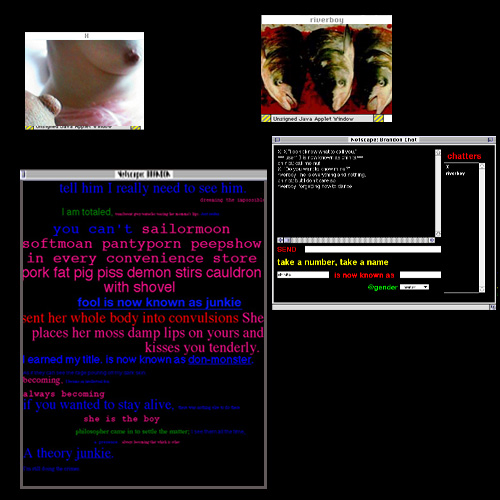

The interfaces in Brandon—bigdoll, roadtrip, mooplay, panopticon, and Theatrum Anatomicum—are each a launch pad, a collaborative platform. Each interface is programmed as a mainframe, a structural construct while the contents and the inhabitants can move in and out in flux. While the programming language is definitive, the narrative shifts and progresses with more add-ons and plug-ins.

Yes, I do come from a video installation and film production background. In films, my narrative is parallel, non-linear. In installations, I also have multi-streams narratives proposed by the collaborators. I leapt into netspace (digital is a recent term), bypassing the CD-ROM format, where I see the streams converge with open circuit possibilities.

Brandon, Interface / Intervention

Brandon, Mooplay interface,

collaboration with Francesca Da Remini, Lawrence Chua, Pat Cadigan, and Linda Tauscher

Materially, did you have to consider the technology platforms on which Brandon would be run? Where did the images that appear onsite come from (were they all culled from the internet? / of digital or physical origin)?

Yes. Surely. Please also remember Brandon is a multi-artist, multi-site, multi-institution collaboration. Each interface is a design/programmation with others, mostly working with, i.e. Javascript and Java applet. Today, many of these programming languages have been updated, i.e., AV streaming. Many images are works by various designers (i.e., Jordy Jones, Auriea Harvey). There were also actual court documents from the Brandon Teena trial.

Brandon, Theatrum Anatomicum interface,

collaboration with Waag Society: Mieke Gerritzen, Janine Huizenga, Yariv Alterfin, and Roos Eisma

Installation view, Theatrum Anatomicum, 1998

Installation view, Guggenheim Soho, 1998

There are several interfaces and the architecture of the site itself is discoverable by interaction. I had the sense that I was finding fragments of an identity. What were you thinking when you created those interactions, different interfaces, and pop-up windows? Was the piece envisioned primarily as web-based? How did you modify the piece for the video wall installation? Did any of your conceptual tenets adjust for its physical mode?

Brandon is like a puzzle? I guess. It was deliberately designed with no easy/clear marked icons to help you navigate through the site. One's ability to investigate, negotiate with the mouse(over) brings different experience of the work. Within a one year stretch, which includes installation, live chat format, actual/virtual performance, no one (including myself) can claim to have viewed the entirety of this work. Pop-up windows on the roadtrip interface, cells of panopticon interface, are allen expansion of the space, spaces to be occupied by various narratives and inhabitants. Surely, non-linear and non-conformative.

Yes, the work was conceived for the web space. However, there remains the necessity at the time to have a real space for public interaction. The exhibition at the Guggenheim Soho's multi-screenwall is a direct translation of the website with kiosks for mouse interaction. I was also able to create installations that 'bridges' actual/virtual with the Theatrum Anatomicum installations set up at Waag Society in Amsterdam from 1998 to 1999. The opportunity to work with the Institute on Arts and Civic Dialogue in collaboration with Harvard Law School allowed for the realization of actual/virtual court rooms scenes in "Would the Jurors Please Stand Up? Crime and Punishment as Net Spectacle." I guess I would have done it if there were no real space offered. But with the real spaces, they offer great chances to merge the actual/virtual public.

What was the response to the piece when it appeared? When did it go offline and were there specific reasons it went offline? How does not being able to see a piece impact its existence?

There was great enthusiasm about this work, for its grand scale, its unprecedented approach to web art. It has been used a lot by media art students and there were several Ph.D. dissertations based on this work.

The Brandon website started out with a sponsored server which was terminated. Then, it was moved to an in-house Guggenheim server managed by its IT department. Around 2005, there was a great reconstruction effort with some funds for digital preservation. It was also brought back in two media art exhibitions, one with Rhizome at the New Museum and the other in The Art Formerly Known As New Media at Banff Canada. In this past year, the website was offline (I don't know for what reason, exactly) and created much confusion for media art studies — I constantly received complaints about it.

Recently, there are efforts to restore this work online by the Guggenheim's collection and curatorial departments. A rather long story, indeed.

For more on Brandon in Rhizome, see an 1998 interview between the artist and Alex Galloway and the piece's entry in the ArtBase.