When visionary engineer J.C.R Licklider published Man-Computer Symbiosis in 1960 — a paper outlining how man’s intellectual productivity can, and should be significantly increased when partnered with a computer — the creative problems of contemporary artists were perhaps furthest from his mind. But during the 1960s, a digital fever struck the art world. Large numbers of enthused European and North American artists, curators, and theorists focussed their attention on the creative potential of computing. Software, systems, and concepts were tried and tested, and a decade’s worth of activity culminated in two landmark exhibitions: Jasia Reichardt’s Cybernetic Serendipity at London’s ICA and Jack Burnham's Software: Information Technology at New York’s Jewish Museum.

Two artists with retrospectives currently showing in the UK caught that initial wave of innovation: German born and New York-based Manfred Mohr, and British born, and still UK-based Ernest Edmonds.

Originally a painter with Constructivist sympathies, Edmonds turned to computer-aided algorithmic painting in 1968. Light Logic, his career-long retrospective at Site Gallery Sheffield, UK, combined early ‘70s works and original punch cards with a new motion sensitive installation and later video pieces. Edmonds’ essential project is an investigation into the variant formal possibilities of a two-dimensional square. In each work the internal bounds of that shape are divided into sectors made visible by the distribution of colour, or the placement of a line. This is a process facilitated by programs designed to filter through combinatorial permutations, defined by Edmonds, until a suitable variation is found and then rendered by hand. A collection of numbered ink drawings from 1974 and 1975 capture the result of this procedure in the exhibition’s only monochrome (black and white) works.

Shaping Forms, Ernest Edmonds, 2007

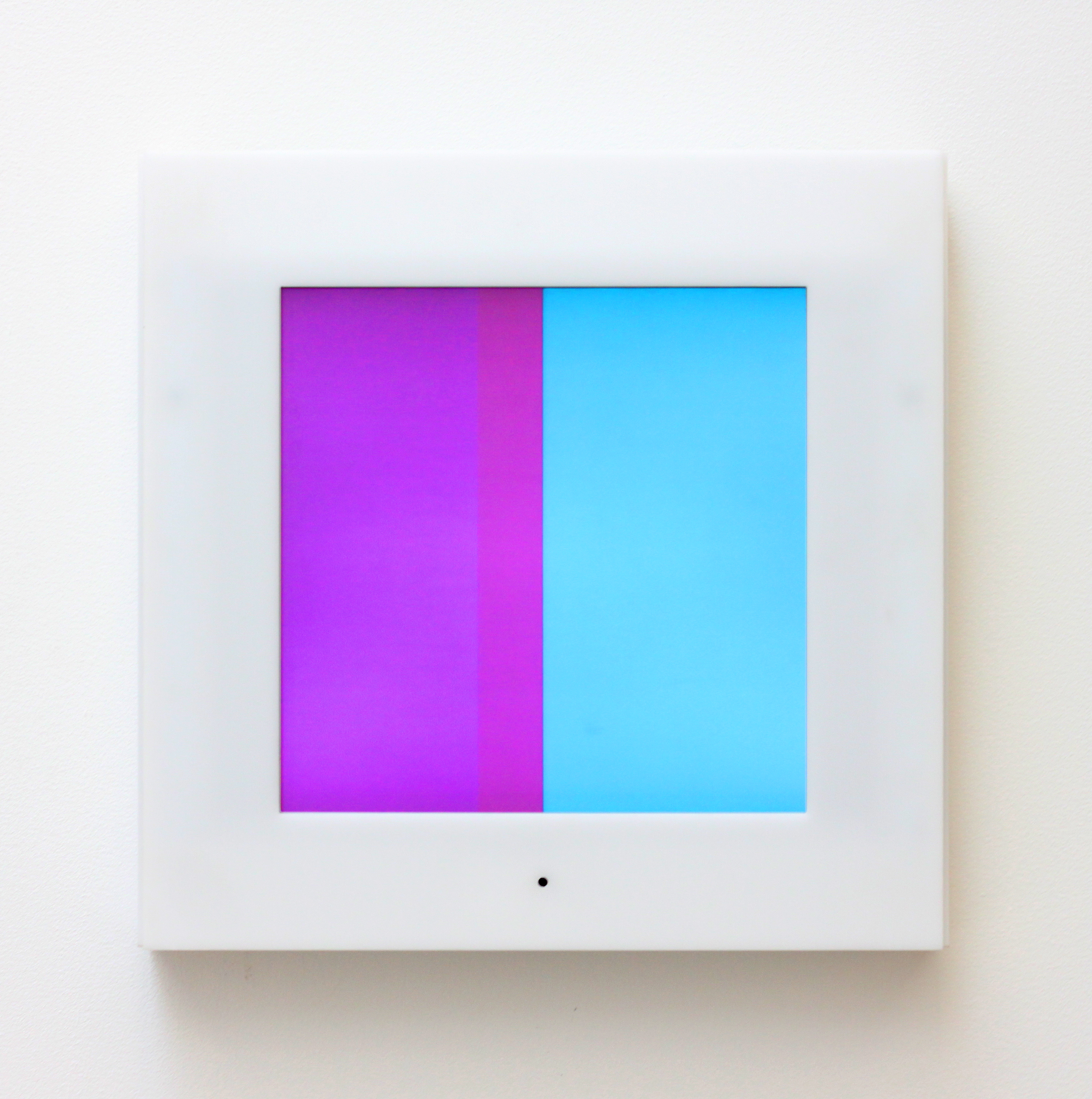

The late ‘80s saw Edmonds move from canvas and paper to video. Here the algorithmic process unfolds in real time. What we see are the formal results of a continuous stream of values produced by a program running calculations Edmonds designed. Shaping Forms (2007) is a collection of three videos that brings Edmunds’ data-centric concerns back into the environs of colour-field painting and Abstract Expressionism. Each of these works focuses on a distribution of color separating the screen into two sections divided by one or two vertical lines. The works resemble quantised, or snapped to grid, interpretations of Barnet Newman’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue series. Shaping Space (2012) is a two-screen installation that runs through squared permutations in response to the movement of bodies within the gallery space. It is an affecting and immersive work that absorbs viewers and bathes the gallery in washes of deep red and amber.

Shaping Space, Ernest Edmonds, 2012

Mohr’s engagement with computing and generative processes began with nocturnal usage of the automated drawing machines (or plotters) of Paris’ Meteorological Institute in 1969. Teaching himself the programming language FORTRAN IV Mohr set about creating algorithms that would result in a series of values the machines would render as forms. The results are delightfully complex images containing an internal logic and symmetry that is both mystifying and simultaneously intuitive, like complex contrapuntal music. In that sense looking at Mohr’s plotter drawings is similar to listening to Bach’s masterful variations on a single theme in the Musical Offering.

One and Zero installation view

One and Zero at Carroll/Fletcher gallery in London presented works from Mohr’s early plotter drawings to recent video pieces, providing a compelling insight into the development of his singular art. The basement galleries presented an array of early plotter works like P-18 ‘Random Walk’ (1969), a cat’s cradle of zigzagging lines against a black background, and P-36g ‘White Noise’ (1971), a series of small angular forms arranged like a hieroglyphic alphabet. The most startlingly piece in this space is a 16mm film titled Cubic Limit (1973-74). In 1972, Mohr decided to focus his investigation on one geometrical form and chose the cube. Cubic Limit is an animation of a three-dimensional cube that is rotated, multiplied, divided, and abstracted for four minutes. There is something luminously supernatural about the film, capturing, as it does, a digital process transferred to an analogue broadcast medium. Whereas digital film often flattens what it depicts, celluloid has a tendency to round out, or materialise objects it projects. Watching the film unfold within the darkened gallery space there are moments when the cube seems to hover as physical matter in air.

Cubic Limit, Manfred Mohr, 1974-74

In 2002 Mohr begun to use color in his works. The ground floor provides an overview of this development from the five canvases P-709-B5 (2002), to LCD monitors showing slow-mo exploded views of cubes in pieces like P-1411c (2010) and P-777f (2004). A set of lacquered steel wall-based sculptures are also displayed, and both P522d (1997) and P-511J (1996) are angular distortions of a cube that bare an affinity to what graffiti artists reach for in ambitious abstracts and burners.

If Light Logic, and One and Zero revealed man-computer symbiosis for early practitioners was a process of delegated number crunching, at the Harris Museum in Preston, UK, artists including Mark Amerika, Sophie Calle, Korean Lee Yongbaek, and Japanese multimedia artist Takahiko Limura revealed a more irreverent, ludic, and improvisatory contemporary relationship to digital technology. The curatorial process behind Digital Aesthetic 3 – the third and final in a series of exhibitions the museum organized in collaboration with the University of Central Lancashire, UK – began with the premise, or rather the truism, that digital technologies have become a ubiquitous, essential, and inescapable feature of modern life in the developed world. From this point of departure both established and emerging international artists who engaged with the digital were invited to take part.

A I U E O NN, Takahiko Limura, 1993/2012

Amerika’s offering The Museum of Glitch Aesthetics (2012) made use of the museum’s traditional mahogany frame and vitrine environment by placing small LCD video screens of glitched, stuttering footage and framed still images, similarly treated, amongst its permanent displays. Amerika’s project sought to represent the life and works of a fictional artist named “the artist 2.0”. These interruptions to the museum’s narrative functioned like instances of noise within a fixed system, an attempt to glitch the collection. Other artists dealt with visual distortions. Limura’s A I U E O NN (1993/2012) used multiple screens to display warped variations of his head pronouncing one of the Japanese vowels, whilst Mary Lucier's North Dakota Mandalas (2004) used processed film footage of four geographical locations to create a psychedelic installation of kaleidoscopic landscapes. On balance the artists within Digital Aesthetic 3 showed a playful engagement with the digital, and it was left to art-sleuth Sophie Calle to turn in a darker mediation on voyeurism with Unfinished (2005) a video work made from ATM security photographs and stolen surveillance tapes.

Loosely book-ending a historical narrative of digital art, Light Logic, One and Zero, and Digital Aesthetic 3 showed that artists’ relationships with computers has evolved from delegated arithmetical tasks to today’s collaborative engagement with software, apparatus, and the ever presence of digital media.