Simon Denny, Those who don't change will be switched off, (2012)

A TV set burns fiercely. These are the last days of the British analog television broadcast.

I kid you not, the United Kingdom limps sorely behind on digital conversion. Luxembourg was first to the finish line, followed by most of Europe, the States, North Africa, Japan. The UK, a chain-smoking marathon runner, who might or might not have gout, has decided — to hell with the lot of you — to race dressed as Chewbacca.

As we drag ourselves sodden and bronchial through those final steps, a slow clap from the ICA gallery greets us. The exhibition 'Remote Control' (April 3, 2012 - 10 June 10, 2012) marks the end of the analog signal by uniting works that take TV and break it apart.

Artist David Hall set television ablaze in 1971. His TV Interruptions were broadcast during normal BBC scheduling in Scotland. No announcement, nor explanation. A tap in the top right-hand corner filled the screen up with water as if it were a cross-section of a sink, a man filmed out at the audience from inside the set, a television burned to cinders in an open field. Each short film held its own during broadcast with a cool irony. Yet the creation and destruction of illusions simultaneously undermined the tyranny of any box masquerading as a window into reality. Hall pioneered art in television and continues to work with the medium and concept. With it, and in opposition to it, for the artists in 'Remote Control' hold their enemy close.

Still from David Hall, TV Interruptions (Tap piece) (1971)

Commercial broadcasting is the adversary in Television Delivers People (1973) by Richard Serra and Carlota Fay Schoolman. A six and a half minute credit roll tells us merrily that we are the end product of TV, delivered through broadcast to be consumed by advertisers. The medium itself emerges banal, or shrill; the mechanisms of corporate control form the malevolent baseline. Screened in the ICA alongside these works by Hall and Serra as well as Gerry Schum, are further exposés on television advertising from TVTV, misogyny from Joan Braderman, and violence from Marcel Odenbach. Sixteen CRT televisions line up neatly to show us how artists rankled with the system over the decades past.

It doesn't sound very radical does it? The wit of Interruptions has already been dampened by their removal from the broadcast context. They confront an engaged, expectant audience, not their passive target. Can we understand quite how difficult it must have been to infiltrate the mainstay of the British broadcasting industry, the BBC, when there is such a multitude of platforms available today? Should an institution that holds the contemporary at its core not be addressing the hidden power lines of the mass media that immerse us now?

"Sooner or later, everything turns into television."

― Professor Sanger in J.G. Ballard, The Day of Creation (1987)

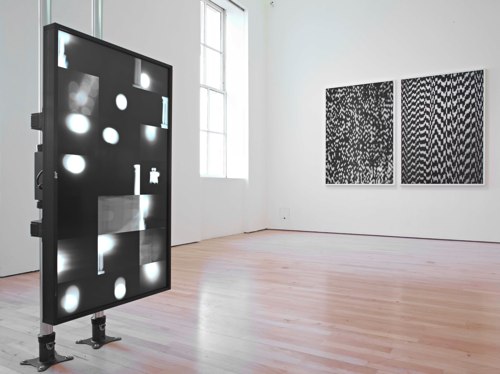

Simon Denny proposes an answer. He has dropped a decommissioned analog television transmitter squarely in the centre of the space. The fortified cabinets of circuits, oscillators and amplifiers all but fill the ICA's downstairs gallery; the solid mass of this engineered equipment heavy in its obsolescence. Just as Hall undermined the implied reality of moving pictures four decades earlier, Denny exposes the mechanics of the signal that has invisibly invaded the nation’s homes until now. Alongside Ira Schneider's (1971) Center for Decentralized Television, an enlarged pen and paper drawing that fills the back gallery wall, Denny's contribution shows visitors the machine behind the specter. His work suggests a direction. For there are gadgets and phantoms that form our current broadcast networks that could also do with an ousting. The ICA does not set about to track a new mutiny with its current show, but the implication is, at some point, it will.

Simon Denny, Channel 4 Analogue Broadcasting Hardware from Arqiva’s, Sudbury transmitter (2012)

Upstairs, the awkwardness of television machinery is left below, and so too a little hostility. Mark Leckey's Felix Gets Broadcasted (2007) takes the image of the earliest test broadcast put out by a New York station in 1928. The silent-era cartoon character Felix the Cat, modeled in papier-mâché and spinning on a record turntable, had been television's first star. Leckey reframes the story, borrowing his title from an episode of the cartoon series where Felix is transmitted through telephone wire to Egypt. Leckey has consistently mined the history of television broadcast for the enigmatic and the peculiar. Taken from their context his plundered images celebrate the eccentricity of television, the first breather the exhibition's maligned medium of choice has had so far.

Format too is given more space upstairs and works manifest as sculpture, video, screenprint and installation. Forty-two hand-held shots of the moon over a clock tower instantly scatter the viewer's gaze. Dividing the frames over two screens installed at a distance from each other, Hilary Lloyd's Moon (2010) exaggerates the minute, subconscious eye flickers of television watching into bodily movement. The artist gently hands back a scrap of self-awareness and so, control, to a screen-locked audience.

Image: Tauba Auerbach and Hilary Lloyd

Installed adjacent to Moon, Tauba Auerbach's large-scale C-type prints of analog static capture a television screen as it attempts to make a picture of surrounding electronic noise. In observing a moment when analog becomes digital, just as the ICA marks this point in time, Auerbach elegantly reflects this transition and provides some concision on the exhibition itself. Her viewer, like the TV set, attempts to shift the random information into patterns, just as the audience of 'Remote Control' is left to make sense of our fragmented and uncomfortably recent broadcast history. The ICA shows television broadcast to be a fertile, but evasive point of artistic investigation. TV is dismantled, but the pieces not yet discarded.