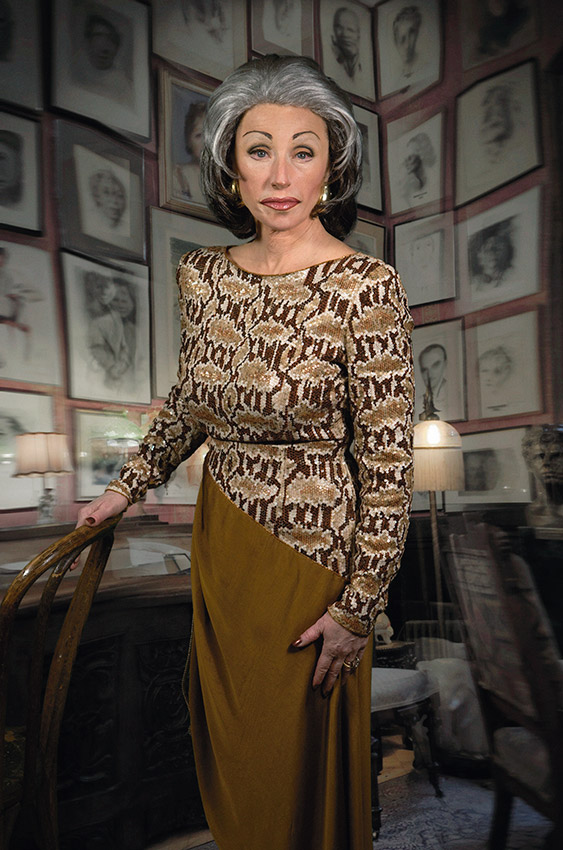

Images from Cindy Sherman's society portraits series (2008.)

Images from Cindy Sherman's society portraits series (2008.)

A friend recently recounted an anecdote about teaching Cindy Sherman’s work to her undergraduate students. She was in the middle of her lecture, explaining Sherman’s elaborate, chameleonic process of casting herself in various roles in her photographs, when one student interrupted, insisting that the photograph projected on screen must have been Photoshopped, that it was impossible that the woman in this image was the same person as in the one before. The others nodded in agreement. Faced with this chorus of disbelief, my friend checked her notes: the image on her slide was from the mid-1980s, several years before Photoshop’s commercial release. The process of creating it was, indeed, analog: the photograph was shot on film, and Sherman’s apparent physical mutation in it the result of costuming and skillfully applied makeup rather than digital manipulation. However, the students’ responses raise interesting questions about how we might conceive of her work in the wake of the digital, particularly since her most recent work has, in fact, made use of such software.

For those of us who first encountered Sherman’s photographs before “Photoshopped” became part of the vernacular, her work carries rather different connotations: it is less about a process of editing or altering the image than one of altering the self through a kind of private performance staged for the camera. Sherman transforms herself, in each image, to the point that she is not only no longer wholly recognizable, but also no longer present as “Cindy Sherman” at all, instead appearing as a litany of characters and stock types. As she noted in an interview with filmmaker John Waters in the catalogue of her current MoMA retrospective, “Before I ever photographed it, I was playing around in costumes and dressing up as characters in my bedroom.”

It is precisely this aspect of dressing up—of adopting and embodying different types—around which much of the critical reception of her work has revolved over the past decades. Moreover, she has maintained a rigorously private studio practice throughout her career, rarely, if ever, working with assistants: Sherman is not only photographer and model, but also hairdresser, costumer, makeup artist, and prop stylist. She performs in front of the camera, but also behind it, adopting multiple roles and functions over the course of creating each photograph. When presented in serial form, the photographs reveal the meticulousness of her process, with each successive image calling further attention to the laborious transformation involved in creating the one preceding it.

Yet over the past decade, Sherman has increasingly embraced the digital, resulting most recently in works that do, in fact, achieve their transformative effects through Photoshop rather than prosthetics, makeup, and careful staging. Her experimentation with working digitally began with the “Clown” series (2003–04), for which she added lurid, patterned backgrounds to images initially shot on slide film, and culminates in the large-scale untitled wall murals she began in 2010, one of which lines the entrance to her MoMA exhibition. In them, her bizarre characters are inserted into a pixelated black-and-white landscape, where they hover flatly against the crudely rendered trees. Moreover, she wears no makeup, transforming her facial features exclusively through digital means, suggesting that Sherman has steadily shifted the orientation of her practice from performance to post-production.

In addition to the murals, the MoMA show includes Untitled #512 (2011), part of a series commissioned by POP magazine, which depicts a figure set against a trompe l’oeil backdrop of a craggy landscape digitally altered to resemble paint on canvas. While these works are overtly manipulated, the use of digital means is more subtle in others: the “Society Portraits” (2008), which cast the artist as aging doyennes, appear less obviously edited than uncannily off. Up close, signs of digital intervention become more apparent: rather than photographing herself in situ, Sherman adds the backgrounds after-the-fact, resulting in awkward, claustrophobic compositions. Wrinkles, pores, and other signs of age are enhanced, making them unabashedly visible.

In one sense, this is a logical step: on a pragmatic level, working digitally offers a quicker, easier way to achieve the same effects—as Sherman noted in a New York Times interview, “it’s horrifying how easy it is to make changes” using Photoshop. It also opens up new possibilities, allowing her to experiment with techniques previously unavailable to her, such as inserting multiple figures into the same image, or placing them in unfamiliar settings. However, for an artist whose work has long been tied to her process, the implications of such a shift seem significant.

Sherman’s photographs have always been ontologically complex, challenging our ability to properly categorize them: they are photographs of Cindy Sherman that are also, simultaneously, not photographs of Cindy Sherman, portraits of the artist in which she is both present and absent. From the beginning of her career, her photographs have insisted upon the constructed nature of images, their potential to manipulate and lie to the viewer, yet they have been anchored by the fact that, on some level, everything in them has actually occurred—she is not a clown, nor an old Hollywood vamp, nor a Renaissance Madonna, but she has dressed like one. The illusion is never seamless: we see incongruous details (a shutter cord in her hand, an obvious prosthesis) that call attention to the fictitious construction of the scenario depicted, but nevertheless, such details also serve to highlight the fact that Sherman has actually constructed it in real life; they are not just images, but documents of her activity.

The digitally altered photographs, too, call attention to their fabrication, but the terms have changed: they lack the implicit tension that underpins the earlier works, between Cindy Sherman as artist who constructs the tableau and Cindy Sherman as model who effaces herself in the image; between the knowledge that the scene is staged and yet, that it has also taken place. Part of what has always been so captivating about her photographs is exactly what made my friend’s student insist that they were faked: no matter how convincing her costume, her staging, her makeup, we know that the same woman lies underneath it.

What to make of this turn toward the digital? In spite of her embrace of software, Sherman’s work is still made for the gallery rather than the screen. Just as the “Film Stills” mimic the old promotional stills produced by movie studios not only through style, but also print size and paper type, the “Society Portraits” echo the gaudy, overlarge scale of a wealthy patroness’s portrait, resembling the sort of thing that might hang in one of her subjects’ living rooms. Even the murals, though they escape the frame, are resolutely oriented in the material, quite literally bound to a physical space.

At first, I couldn’t help but feel that by exchanging the elaborate masquerade for Photoshop, Sherman was, somehow, cheating. But perhaps this new direction is fitting: though they have often been read in terms of performance, Sherman’s photographs have always been, at their core, images about images: about the way images function, how they are created, trafficked, and coded, the ways in which they manufacture and disseminate meaning. Now that Photoshop has become the norm, we know better than to have faith in their fidelity—we assume that what we see is mediated, altered, and edited, regardless of whether it is an Instagrammed iPhone snapshot or an airbrushed celebrity on the cover of a magazine.

Throughout her career, Sherman has been singularly attuned to the cultural role of images, and her digital works, too, capture and comment on the way we understand photographs today—not as documents of reality, but as raw materials that can be endlessly refashioned.