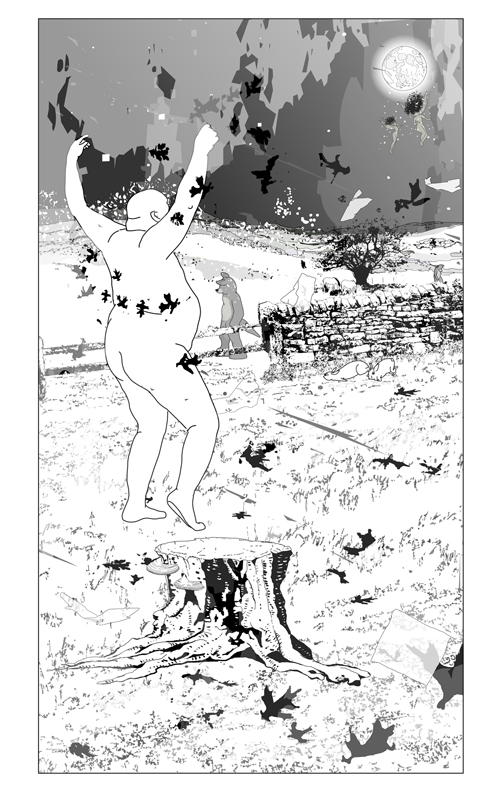

Mesocosm (Northumberland, UK), Fall (2011), Flash standalone application

Mesocosm (Northumberland, UK), Fall (2011), Flash standalone application

You describe your work as making psychological narratives about humans and their relationship to animals, plants, and the weather. It might seem surprising that this relationship to the natural world is depicted via computer animation. How do you perceive the use of technology in order to describe the natural? What does the computer offer you specifically when thinking about nature or the natural?

All representations employ some form of technology—start with burnt charcoal on cave walls.

Why the computer? Why suck all this electricity out of the wall to make inquiries into the representation of climate change? Why pick animation, which is a most unnatural form? There are tools and aesthetic choices that I naturally gravitate towards—in this case, scalable vector graphics that I can make move.

My work started as pictograms and cartoons, leveraging the language of signage and the cute, because cartoons and info graphics are sly. Animation has freedom from verisimilitude, and warrants the fantastic. I’ve remained interested in making work that leaves you (and me) unsure if it’s clip art or hand-drawn, work that sits between the handmade analogue and the digital.

Much of the work I make is keyed to internet research, obscure stories, contradictory data, and highly circulated media. The Poster Children was made in 2007 when the polar bear became the poster child for global warming (Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth) and the poster child (again) for the cutest (Knut, born at the Berlin Zoo), and it was also the year of the Virginia Tech shooting which spawned copycat killers’ electronic press kits on YouTube, anti– and pro– gun law campaigning, and racism (questioning whether an Asian has the right to perpetrate this sort of massacre which has historically been the territory of young “pink” people). This work strategy sprung directly out of the network of information, personae, and cultures that exist within an internet ecology. My work is about the networked stories we tell ourselves about our place in the larger world, the interwoven and often conflicted threads of this, and how these are represented in mediated form. The network thinking emerged directly from distributed computing, systems, and game design, and this newish, lateral (non-hierarchical) web of connections. Animation—highly constructed and artificial worlds—is a good vehicle to explore this.

Your recent work, Mesocosm (Northumberland, UK), truly considers online viewership: on your website, you describe its running time as a 146-hour cycle that begins on a certain date and runs until the viewer closes his or her browser window. Other works, like the site-specific Paradoxical Sleep series, or Slurb, which originated as a public art work, are presented on your website only as excerpts.

The web is obviously a freer space for publishing than sanctioned venues of museum galleries, movie theaters, or television. When it’s appropriate to make works for the web, I do. Not all work benefits from this context. I post clips of all the movies, even if they don’t look perfect in that scale and compression. They are posted as references to the larger-scaled formats. The Mesocosm series is not great at the browser scale, but it’s okay. It was not designed specifically for a browser viewed on a small monitor, and as there is a lot of detail in the distance, it is actually best seen at a larger scale. Mesocosm is meant to be lived with, to be returned to or passed by repeatedly (for instance, in an office, a living room, or a commuter space). If you leave it running, you’ll witness subtle but significant changes in season, population, and behaviors. If you close the browser window or quit the application, the “winter cycle” version of the piece will remember where you left off.

Do you plan on further experimenting with online presentation of your future works?

I am working on a collaborative set of “survival” instructions, whose main delivery system will be a web site comprised of PDFs and audio files. It all depends on what project-specific context the web can offer.

Your work and its presentation both deeply consider the way we experience time and duration. Do you consider the amount of time that people spend with your work as crucial? Do you think time-based work and its new channels of distribution have changed this?

Since I made Braingirl, I became intrigued with different kinds of viewer attention. Web viewers tend to do more than one thing at once, so I started building what I hoped would be aggregated narrative structures that didn’t depend on continuous viewing to follow a story thread. I started building dense layered narrative works that you might return to repeatedly instead. It is logical for me to move towards longer works, less and less music video-sized experiences, and pieces that are not authored Quicktime movies but rather unfold procedurally.

Something about your working in thematic series invokes in me a certain idea of nineteenth-century science in its taxonomical nature, especially in the recent series about invasive species (Heraldic Crests for Invasive Species, 2011). Your work is heavily research-based, which can be traced on your blog, and is closely linked to the place in which it is produced or conceived. Do you see a scientific character in your process?

The character of my process is generalist and heterodox. Scientific projects are most often expected to perform consistently, and use recognized, homogeneous method. I think I address most of my work as tackling a problem, and problematizing a scenario or issue through design. More than emulating science, I’m interested in the history of natural sciences and its connection to other histories, philosophy, art, and narrative; the mediated stories of the natural world (not just Western versions) and how mediation and interpretation rely on visual strategies to do so. Can I utilize well-worn aesthetic strategies to make new pictures or new propositions? At best that’d be a new vision that addresses the romantic divide and reconfigures the relations between humans and the rest of the biosphere, and might suggest a different time frame for events beyond the human.

Age:

“Ladies” (of all genders) can opt out of discussions about age or money.

Location:

Brooklyn, NY.

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

Depends on how you define technology. I studied video art and installation in school. I participated in the BBS EchoNYC in 1992. In 1994, I built my first website and worked at SonicNet.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them?

It was through web work in the mid 90’s that I started animating, first gif animations and then Flash v1.0. Before that, I made experimental videos and films, as well as graphic design projects. My work has always been collage- and bricolage-based, even though it appears as a fairly coherent and authored field now. I started using more and more rotoscoping (drawing frame by frame on top of video) in the last 4 years, but I also use more standard cartooning—squash and stretch, tweening of shapes, and purely invented behavioral cycles.

Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I have a BFA from School of Visual Arts. I studied traditional fine art media, installation, video art, and semiotics. I was technically a sculpture major.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

I make drawings, and most recently completed a series of letterpress prints. I try to use media appropriate to the subject matter, or media that extends the narrative content. For instance, cartoons are a great way to create speculative fictions, moving paintings, and uncomfortable subject matter. Letterpress is an old technology that was used to create heraldry and identity work (like monograms), so it was perfect for the updated Heraldic Crests for Invasive Species. These were originally hand-drawn, then inked on the computer with patterning added, and then metal plates were created and a traditional printing press was used.

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

I have intermittently donated design services for activists. I am completing a new body of work this winter about petroleum, and hope that an animation on the explicit connection between drilling for oil and water poisoning will be useful to activist organizations.

What do you do for a living? Do you think your job relates to your art practice in a significant way?

I’m on faculty at ITP.

Who are your key artistic influences?

It’s often project-specific, here are some: Odilon Redon, Philip Guston, Chris Ware, Hannah Hoch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Sue Williams, Marcus Coates, Hokusai’s Manga, Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, Lucas’s THX1138, Lynch’s Blue Velvet, Wong Kar Wai’s Fallen Angels, Herzog’s Grizzly Man. Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, Michael Pollan’s Botany of Desire, the writings of Stephen Jay Gould, Norman Klein, and Mike Davis, Dale Pendell’s Pharmako trilogy. Thomas Bewick’s wood engravings, anonymous instructional design, early botanical manuscripts, and so on.

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

Katie Salen, Nancy Nowacek and I made a project for 01SJ in 2006 called Karaoke Ice (which then toured Los Angeles through LACE in 2007). I’m starting work on a set of instructions (sound and graphics) for 2013 called Survival Challenges, with Ruth Ozeki (novelist and Zen priest), Oliver Kellhammer (land artist and botanist), Una Chaudhuri (ecocritic, drama and English professor), Fritz Ertl (theater director and drama professor), and a PTSD specialist.

Do you actively study art history?

Yes—I see a lot of exhibitions, many of which are historical. I try not to draw lines around what constitutes art, so I would include natural history exhibitions (and their construction), movies (fiction and documentaries), performance, experience design, graphic and identity design, historical frameworks for things like botanicals or ethnography, and so on. I have studied a bit on Asian traditional screen and scroll painting, and book design.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

Recently my reading has been more in the ecocriticism vein, and I got really excited by Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter. I’m planning to study some Bruno Latour and Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) this fall. I was very influenced by Deleuze and Guattari’s work on Becoming Animal and all the works they influenced, such as Steve Baker’s The Postmodern Animal. Mesocosm was strongly informed by Timothy Morton’s post-humanist writings on nature and on ambient art, (especially the essay “Queer Ecology” and his book Ecology Without Nature. I work with theorist Una Chaudhuri on presentations and projects as well.

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

“New” media shouldn’t be ghettoized. We need more dialogue between various forms. At the same time, while there are more funding opportunities for new media now than there were even five years ago, they are often a sub-category in interdisciplinary or film/video categories.

In my own work, even though I have and will make objects that contain screens, my IP does not reside in the objects made as much as in the work inside the screens. I’ve had a challenge editioning flexible formats—for instance, I edition an animation by pixel resolution, and one edition might comprise a projection, a flash-player and monitor, or just a USB stick. It’s a relief to work on a set of letterpress prints or series of porcelain plates.