James Bridle, a publisher based in London, is a member of a rising class of digital futurists that fuse multiple professional experiences—for him, a university degree in Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence with an organic interest in literature—to form a dynamic public-facing practice. “Essentially, when any new technology comes along, I try to force literature into it in some way,” he wrote during our recent email exchange.

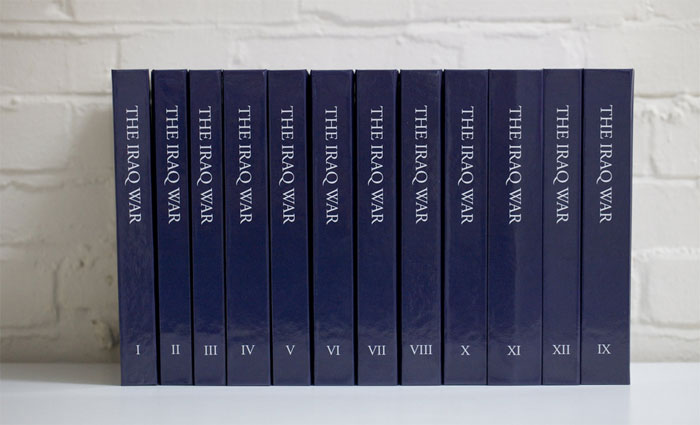

The Iraq War: A History of Wikipedia Changelogs (2010)

The Iraq War: A History of Wikipedia Changelogs (2010)

Bridle runs the conference gamut from book fairs and South by Southwest to the UNESCO World Forum on Cultural Industries in Lombardia, Italy, where he lectured just weeks ago. His presentations are documented on another website devoted to technology and so-called book futurism, http://booktwo.org/, where he posts a series of essays and updates on his myriad projects. The Frankfurt School is an obvious inspirational go-to, given the titles of his posts and projects: Walter Benjamin's Aura: Open Bookmarks and the form of the eBook (2010), The Author of Everything (2011), and Robot Flâneur (2011). Bridle’s better-known efforts include The Iraq War: A History of Wikipedia Changelogs (2010) a twelve-volume set that chronicles, in print, every change made to the Wikipedia article on the Iraq War; Bookkake (2008) is a digital and print-on-demand publishing system for erotic literature, while bkkeepr (2008) and Open Bookmarks (2010) help users track and share their reading experiences through Twitter and social bookmarking.

Artists' eBooks Screenshot

The Iraq War: A History of Wikipedia Changelogs segues elegantly from the digital to the object worlds; the books qualify the data, physically. I see a different, yet equally compelling set of relational possibilities in the project I chose to focus on for our interview—one that I now know Bridle considers a failure (his words; not mine!): Artists' eBooks is, as its title suggests, a digital imprint designed to provide an experimental publishing platform for writers and artists. In the conversation that follows, we discussed the shifting nature of the reading experience from print to screen, and its implications for the book-as-medium.

SH: In thinking about the mimetic attempts of Apple’s iPad/iBooks app here, in particular, I’m curious about the various ways in which e-reader hardware replicates the physical book in size, shape, and even surface—the physical dimensions of the book are represented digitally by a beveled edge; its animated pages turn with the flick of the user’s thumb. As someone who considers electronic publishing from a futurist’s perspective, how do you see the physicality of the virtual reading experience changing?

JB: I used to think that the skeuomorphism of most electronic book readers was a deliberate, or at least emergent and therefore temporary, phase. I thought people were designing ebook readers like natural mimics: they just had to look enough alike the physical book to kill it, and then they could look like anything. And yet, so much of that design is still with us. The almost-ubiquitous page flip animation is an abomination. Apple’s iBooks is a particular offender: it inserts the image of a stack of pages to the right of the page that implies you're always on the recto and you've always got 200 pages to go, regardless of what you're reading. This is bad design, not only because it cleaves to irrelevant artifacts of the physical book while ignoring the affordances of the physical; it actively impedes them. Electronic reading will be improved the sooner we escape the convention of the "page", but current formats reinforce this.

SH: Agreed on the iPad page flip animation-abomination. I catch myself feeling actively embarrassed by it while reading on the train, accidentally skipping multiple pages and then thumbing furiously to find my spot. How can we escape "the convention of the 'page,' " though? Where do we go next? Do you feel like certain online reading environments or apps—Flipboard comes to mind here—are helping de-emphasize the page-based reading experience?

JB: It's a matter of letting go of physical concerns about the book. Books are written in sentences, paragraphs, chapters and sections; they've never been written in pages. The web shows that text works as a continuous flow at any length or format: I prefer reading Instapaper's accessible, addressable scroll than any fake codex. For some time I've argued that the physicality of the reading experience is a red herring: what matters is its temporality. This has historically been embodied in the book itself, because it has nowhere else to go, but increasingly, with the free flow of electronic texts through the network, with our ever-diverting attention, and the development of new tools for social reading, for annotation and sharing, our experience of the book is separating from the physical object, and with it our focus on the material will pass away.

SH: Hardware developers out there will certainly disagree, as do I! How do you account for the fact that certain types of content is being more readily consumed on the iPad, or that some devices—the Kindle or the Nook, for instance—are being credited with reviving certain markets in the magazine industry? How can we divorce ourselves from the physicality of the reading experience? JB: I'm prepared to be proved totally wrong on this—but I don't think I will. I think this is a temporary blip, a gadget-induced mania that will disappear when the situation normalizes. For naturally heterogeneous formats like the magazine, the web is a far more native land. So, yes, they will work great on the iPad or other connected device, better than paper, but the line between them and the web will slowly disappear. The magazine format—like the traditional book— is useful to publishers as a package they can sell; less so to the reader.

SH: Speaking of packages: Your “Artist’s e-books” project is of particular interest to me, as I’m curious to see artists and publishers negotiate with the form in the digital realm. How are you defining the artist’s book within this particular project?

JB: Artists' eBooks started by defining itself around what was possible using a particular format: epub. Epub is fast becoming the standard format for ebooks outside the Amazon ecosystem, although I admit to being less convinced about its longevity and full adoption than I might have been a year or two ago. It's never good to start any project with a format rather than an idea, but I wanted to see what artists and experimental writers would do with this format that was being widely used for corporate, traditional purposes. I also felt—have always felt—that ebooks should be democratising, but the technology to produce them was being unreasonably obscured. It's a lot easier, financially, for someone to produce and distribute an ebook than a physical book, and I wanted to show that this technology was available to anyone.

SH: The role of the image in electronic book publishing is a complicated one, as each e-reader presents a particular set of challenges in terms of color, resolution, and scale. Given the primary role of the image in many artist-produced publications, how are you responding to these challenges within your own project?

JB: I don't have much to say on this, sorry.

SH: Can you tell me a bit about the process behind the Artist’s e-book project? How did you go about choosing the artists you’ve worked with thus far? Is the process an agile one, whereby author, editor, and developer work together from the ground up, or do you simply convert printed books to digital form?

JB: It's different for each book. The original selection came out of discussions with Tony White, a writer who I've admired greatly for some time. His cut-up works had been published in print as part of exhibition catalogues, but as an ebook they became networked and could be reconnected to the original sources. Niven Govinden's work is infused with music, so we took the opportunity to add a soundtrack, while Kenji Siratori's work is simply unpublishable in any real traditional, commercial form: the position of artist and the format of the ebook allow the work to go out regardless.

SH: Historically speaking, the artist’s book was a rarefied object, qualified as such by a particular set of physical parameters; that changed over time, of course, but the artist’s book still exists as such despite more democratized (and even, dematerialized) means of production and distribution that govern contemporary publishing practices. Do you think the artist’s e-book presents a particular or even greater opportunity to push the physical parameters of digital publishing? If so, how?

JB: I think that if there are going to be interesting developments in literary style they are likely to come about in responses to new technologies; if not, they would have come about before. But I am beginning to think that the notion of an Artists' eBook artificially constrains this possibility. We're not going to find new opportunities by aping the old forms in a new media: the most interesting literary experiments I've seen are taking place fully entwined with the new media, embedded in blogs, wikis and services like Twitter, products of those cultures rather than interventions in them.

SH: How does the notion of an Artists' e-book “artificially constrain” given possibilities in the form?

JB: The traditional book is a closed container. It has many possibilities, but they are enclosed in the single book. The electronic book is no longer closed, it has been unbound. So forcing it back into the container of the epub or other format seems limiting. You can link out, include images and some other media, but you can't embed networked content, like videos hosted elsewhere, or computational or dynamic content, for example. So while artists' ebooks are a totally viable thing, they seem to be a very small subset of what an artist or experimental writer could be doing with electronic technology, and of less interest than either a traditional artists' book, or a more networked approach. For me, the magic is in the network; the ebook shrinks from this. Which is fine for traditional literary formats, but is definitely an artificial constraint on the artist.

Sarah Hromack writes about the intersection of art and digital culture; she also manages the Whitney Museum of American Art’s website. Twitter: @forwardretreat