Semiconductor (Ruth Jarman and Joe Gerhardt) are artist explorers of the natural world, they build installations and moving image with animation and sound drawn from their encounters with prestigious scientific institution such as NASA’s Space Science Laboratories and the Smithsonian Archive as well as journeys to alien places like the Galapagos Islands and Ecuadorian volcanoes.

Two new works drawn from their other worldly travels, Worlds in the Making and Inferno Observatory are now showing at FACT in Liverpool, UK, Peter Merrington talked to the artists about their work.

Peter Merrington: Could you start by telling us a little about your new show at FACT?

Ruth Jarman & Joe Gerhardt: Inferno Observatory (2011) is made from archive film taken from the Mineral Archive Lab; one of the departments in the lab is the Global Volcanism Program. All of the films are donated by Volcanologists who shot them on 16mm cameras when they went out in the field, most of the films are from the 40’s but some go back to 1910. We divided it into three areas, with shots of scientists prodding and measuring volcanoes and doing very gallant things with lumps of lava. And then a section where people are watching volcanoes; mostly scientist’s wives looking very glamorous standing in front watching them. And then there are shots from up in planes circling ash clouds. It is very much about the phenomena of the volcano.

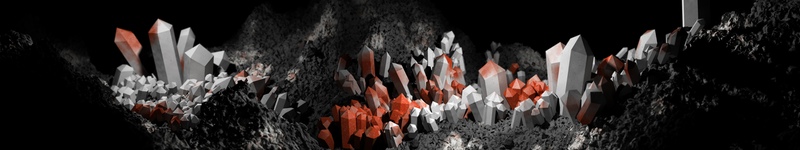

Worlds In The Making (2011) came from our interest in the basic building blocks of the world around us - looking at how land forms. We wanted to go back to the really simple tools and techniques that man uses to try and understand the world around us. With the space sciences work it immediately had a very high tech wow factor and we wanted to go back to simple observation and hand held techniques, so we spent time in Ecuador with some volcanologists in an observatory and the bottom of an erupting volcano.

PM: There is quite a clear progression in the way your work has developed, could you talk about your origins and how your work has developed?

JG: We’ve always had an interest in exploring our surroundings, the landscape in which we exist, the stuff that is around us. That can be architecture and it can also be nature or cosmic space and the universe. We were very inspired by early experimental film, animation and environmental art, artists like Len Lye and the Whitney Brothers. In many ways we are thinking about landscape and those worlds in terms of sound and time and what those things bring to one another.

RJ: When we were at college we started working with the first generation of domestic computers, we saw the potential this offered us in terms of space, the kind of infinite, virtual space to work with the world around us, to control and manipulate it. We started to explore the potential of the work we were making in the real world within the computer. We were interested in the potential of the medium of the computer, in finding out what the computer was and how we could find our own language, as artists, with the computer.

That’s where our name Semiconductor came from; we were making pieces of work were it was very difficult to shake off the computer and the software that was in the work so we realized that there was a kind of partnership between the computer and ourselves.

At that point the computer always had its hand in the process, it’s own signature in the work. We always embraced that and we often gave the computer several opportunities to input into the work, for example, allowing it to choose random colours, shapes or forms - that was very much to do with how restricting the technology was at the time.

Our work has developed along the possibilities of technology and the computer, there were always things that we wanted to do that were restricted by the computer, but now that isn’t so much important in our work, because we can do pretty much anything we want to do.

But we have also always been interested in mans relationship with his environment around him and how we experience that and create an understanding of it.

PM: You often work with experimental sound artists, such as BJ Nilsen and Oren Ambarchi, could you describe the approach you take to using sound in your work?

RJ: With Oren, who did some sounds for Worlds In The Making, we were really interested in how he uses sound as a kind of material. He really plays and pushes and really sculpts the sound.

JG: We want the sound to have a physical presence.

RJ: We are using his music to bring an emotional response to place. Throughout the whole work we play in different ways with how the sound and music control your experiences of place. Oren’s sound is very much used to bring an emotional response to place.

There are many different layers of sound in Worlds In The Making, we collected lots of seismic data that’s been taken from underneath a volcano, they think it’s the sound of magma moving in chambers beneath the volcano. When you speed it up to make it audible, it’s an incredibly evocative sound it sound, almost like hearing rocks scraping and crashing together.

When we were at the Smithsonian Mineral Sciences lab we met a scientist called Bill Melson, who has been recording eruptions from a particular volcano on reel-to-reel tapes for over a period to 15 or 20 year. We went through all of the recordings and have used some of them to animate the environments within the work.

PM: You go on some amazing journeys to make your work, to NASA and the Galapagos Islands and the Smithsonian Archive. They all have a mythical quality, with their own narratives and history, everyone knows these but from the outside…

RJ: The mythical idea vanishes very quickly when you go to those places. When we spent time in the NASA Space Sciences Lab we were welcomed into it and all the mystery seemed to strip away and it became everyday. Very quickly, we could have almost been in a car garage. It’s the people and the process that they are doing that are really interesting; it was the same in the Galapagos.

JG: I disagree, obviously our perception is different when we get there, but there is still a lot of mystery and mythology. The animals behave differently there from anywhere else you’ll ever go, it’s completely unique, and even at the Smithsonian, even after several months, I still had a sense of wonder. I still feel like the scientists are doing magic in a certain way. They are discovering things that are unknown, they are making things happen which are on the limits of comprehension, I don’t know if it does go away.

PM: Through the kind of research you undertake do you see yourselves as scientists?

RJ: I think working in those scientific environments we feel more like sociologists, but in our approach to scientific tools we try to remain as naive as possible. We are trying to give a human experience to those things, for example in our work Brilliant Noise, we used the raw satellite data about the sun, we were not interested in all the other images that we’d seen which were very glossy, colourised and remote from the viewer, the raw data had something that was very tangible.

JG: Whenever we would work with scientists, they would give presentations on their work to their fellow scientists, they would always have these amazing diagrams, illustrations and pictures of their work and they would say, “oh we’re going to skip through that bit, we haven’t got time”. They would never want to look at the stuff we would want to look at. We are bringing our naivety and fresh eyes to it, whereas to scientists it’s the first things they want to push aside.

PM: A lot of the time you represent scientists at work, doing their everyday activities, how do they respond to being presented in that way?

RJ: You get very different types of scientists, and the ones we’ve been working with are obviously very enthusiastic about what we are doing already and they see that reaching out to the general public is a really important thing to do.

When we were in the Galapagos Islands we wanted to film scientists working in the field who were just using very simple techniques and process of observation, using their hands and very simple tools to carry out their science. I think a lot of the time the scientists just think we’re journalists so they just leave us to our own devices, which is perfect because we don’t want it to be acknowledged that we’re there.

We sent the scientist that we’d been filming the work that we’d done and he was like ‘I didn’t realize you were making a film all about me!!’ He was so excited; it was a form of celebration.

JG: He had spent four years counting thorns on brambles! For him, this was a really painful thing that he’d experienced, it seemed kind of pointless to him - there is a bit of a funny joke in there! But to see that someone else could see something in it was really important.

The same was true in Magnetic Movie, one of the scientists in it had a phone call from a fellow scientist, saying “we didn’t know that you were doing these experiments?” but of course they were not real…so strange things happen.

Peter Merrington is an artist and writer from the north of England.