“Between the ubiquity of Internet access and the fact that data has no objective tangible form, internet users have long been plagued with the problem of determining the value of the content they are ingesting.” - Zach Gage

Seen in a certain light, the core of technological mediation has always been presence, absence, and distance. Writing established the possibility of presence during absence, arrows and gunpowder created force at a distance, the telephone created presence at distance, and network computing fundamentally altered the nature of being “absent” or “present” to an almost unrecognizable degree. No small surprise then that contemporary “media art” practice seems to return to these questions as being fundamental investigations. The question of what “presence” could be was explored and expanded throughout the dawn of the internet age: Ken Goldberg’s TeleGarden, Eduardo Kac’s concept of Telepresence, Sven Bauer, Heath Bunting, to grab but a few names. Each possibility of a new field of entry, a new method of retaining, mapping, signifying, and storing, opened a rich possibility. Now fast forward fifteen years and ever-presence is exhausting, a nuisance that forever asks and returns only the vague rewards of a slot-machine and seems to fray our sense of privacy, meaningfulness, boundary, and perhaps even self. So how then to artistically respond to this? Exhibit: Zach Gage.

His works are at once sophisticated and remarkably simple, both in presentation and concept in a way that might be recognizable to Joseph Kosuth or Lawrence Weiner, rather than the Baroque conceptual complexity on display in much media art in the 90’s. Computational art or interactive art has generally taken two tacks in dealing with the complexities of technology itself -- unabashed celebration and dystopian anxiety. At either extreme is the grandiose challenge of prediction: this possible or actual relationship to technology will lead to this consequence or benefit. The reality of living with technology is not only simpler but is often much more banal. The most refreshing element of Gage’s work is how it asks us to do nothing more than consider what is. Working with the instantly familiar data sources, Twitter, Google, chat servers, at their simplest, his work often resembles a refreshingly sharp Occam’s Razor taken to notions of the richness of data and networked experience.

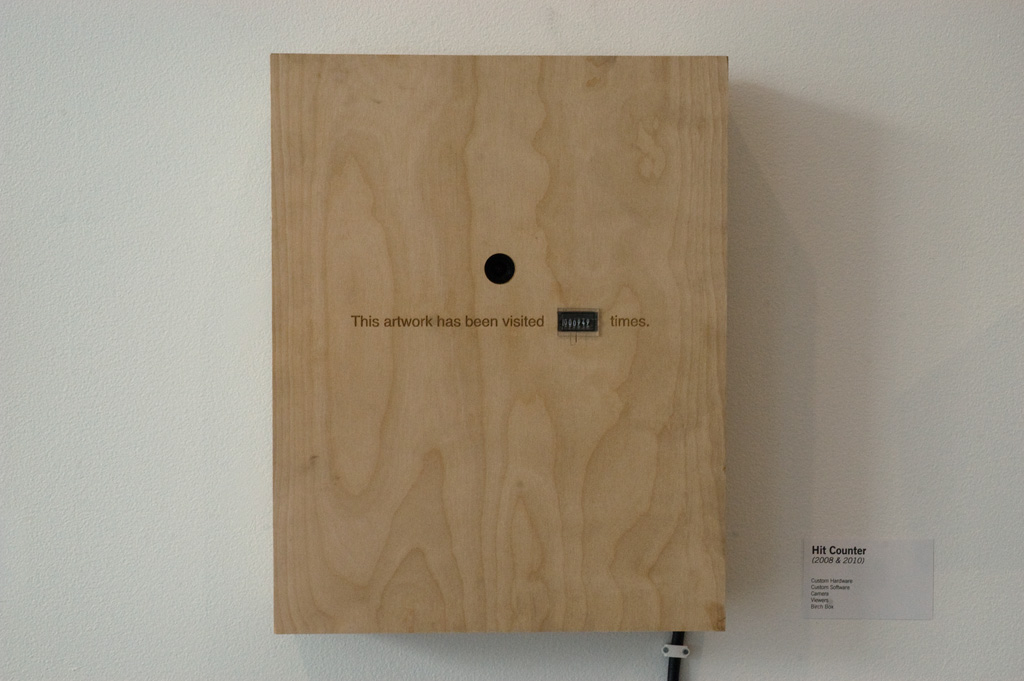

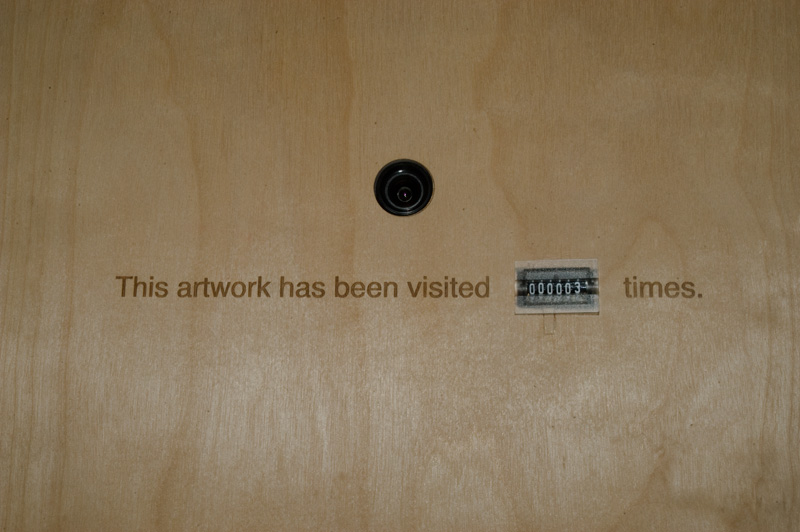

His thesis show, “Data”, is an extremely visually and thematically understated installation comprised of several pieces. Small wooden boxes, wires, and simple placards: none of the forced estrangement, hand-waving interactivity, or spectacle that one associates with computer arts. In particular, one of the pieces in the show, Hit Counter stands out as particularly poignant: a simple measurement of the number of times someone has stood in front of the work. Face recognition software is used to keep track of the actual viewers and the number is displayed on an old-fashioned mechanical counter. Gage states “with no other means to judge it, Hit Counter demands to be assigned a worth based solely on its popularity.” But then, Hit Counter is not merely asking to be judged on popularity. It, like so many things in our media culture, is popularity. It’s nothing else, and it’s not any kind of popularity other than actual physical presence; a sharp reminder of the relationship between presence and popularity. No matter how many people hear about it online, what is written about it, what buzz is generated, it’s a simple box that generates a number based on how many unique people have stood in front of it. I’m not sure whether I’m more struck by the concept itself or that I am so struck by the concept as an ontological exercise: something that simply is actual physical presence. It’s odd that it is odd and, in that oddness, it is a stance closer to Sol Lewitt “Sentences on Conceptual Art” than many other re-interpretations of his legacy and ideas. Reformulating the simplest data object imaginable in the simplest terms has a markedly clarifying effect and in clarification is a rare kind of beauty. I spoke with Zach Gage about Hit Counter, as well as his larger practice.

I’m curious how you view the relationship between your more artistic work and the games that you make. Can you talk a little about that?

I've had a really hard time with this as well. I think the 'games as art' debate has kind of brought this sort of question to the forefront (since I am a self described artist who happens to make games). Really though, I do a lot of different types of projects, and in many cases I can't directly link my conceptual works with my games. This isn't necessarily because some are games and some are art, but more that I'm exploring entirely different avenues with the works.

With most of what you've termed my more “artistic works”, I'm investigating this situation of humanity transitioning our lives into a virtual space, and how this new space gives sort of a physical property to ideas. That we no longer have to make art objects, because online, a conceptual or theoretical object is just as valid as an actual object. Words or code aren't just organizations of thoughts that can give rise to objects, but actual things that can be interacted with in and of themselves.

Most of my games do not follow this line of inquiry. Generally with my games I try to create a system that encourages and rewards the curiosity of a mechanic. I like to keep rules extremely simple but also include a great deal of depth. I do this not just for players but for myself and my enjoyment of creating the product.

I suppose if I had to find a connection I would say that my games are an attempt to create systems that are just as simple, yet complex, as the tiniest fragments of the subjects that I explore with my conceptual works. They're invitations to engage your mind and reflexes in challenges that you'll have to get really invested in to reap the rewards of.

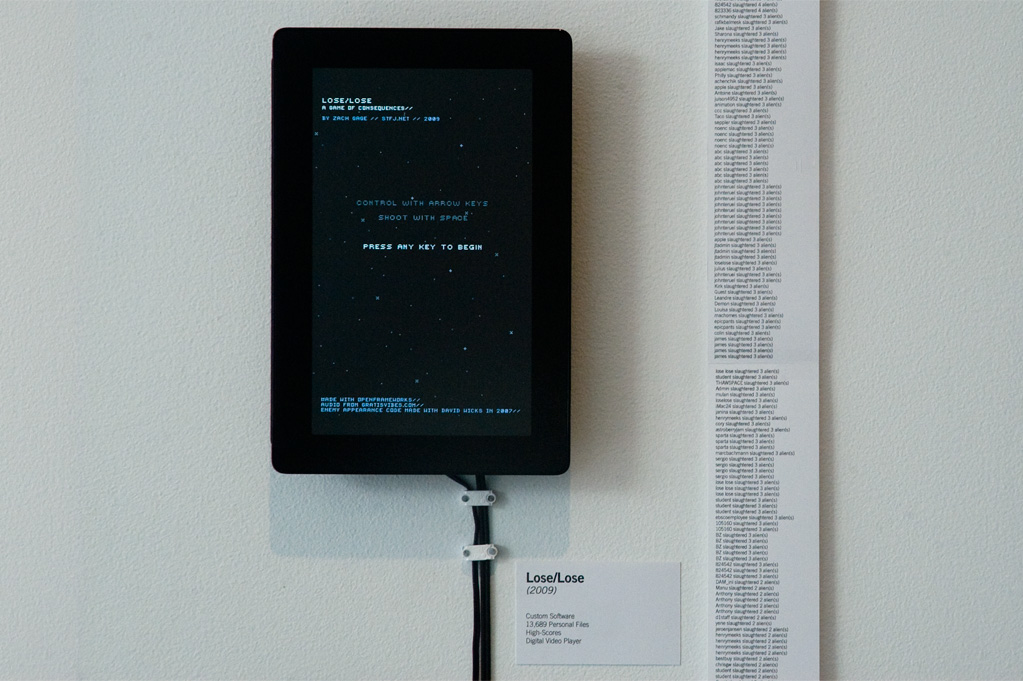

Of course I have to also say that this isn't always the case. Games like Lose/Lose or Killing Spree fit neatly into many of my artistic directions.

What does data and the shaping of data mean to presence and existence? Is data a way of making people present or alive? Is data somehow existential?

What's special about data isn't really data itself, but more the environment that has grown up around data. As a singular thing, data isn't particularly understandable or important. Its significance only appears to us in context.

The most powerful aspect of the internet and computers as far as I am concerned is that they give us (all the users of computers) a shared context.

Chatting to someone online is so different than speaking to someone in person (or even over the phone) because almost nothing is preserved from our physical world interactions. The only parts of that other person that remain are their thoughts and their speech patterns (and even this is often different online). To some extent, we are not even communicating with them directly. When I talk to friends online I'm talking to a program that I have decided can act as a proxy for them, based on their input, and likewise, they are talking to a proxy for me, based on my input. We've agreed on this shared context together. It’s as if we are all playing a gigantic game of pretend, except that it's all becoming real.

Once you realize that this digital world we are living in follows rules that are entirely made up by its users and creators, everything does in fact start to get really existential. I touch on this with a lot of my projects in the data series. If data represents us to one another in context, where do 'we' exist within our data? To go back to the previous example, when I talk to friends online, they're interacting with my data, but they believe (somewhat correctly) they're talking to me. You could argue that I'm actually there, on the other side of the computer responding, but what if this conversation is happening through email, or in a forum? What if it's not even a conversation at all? What if it's some future person digging through my website, reading my Facebook profile, and talking to my historical chat bot? Do I exist within that data? It's a very blurry line.

I’m curious about this idea of networked loneliness: Someone Anyone, for instance, explores the idea of networked loneliness in a very honest and straightforward way that I find very refreshing. I’m curious whether you see loneliness different now than, say 10 years ago?

This is a tough one for me to answer, given my age and experience with the internet. 10 years ago I was only 15 yet I feel that many of the experiences I had when I was that age have fed into most of the work I'm doing now.

It’s very possible that computers have solved all of the abject components of loneliness. When you look up loneliness in the dictionary you find that most of its definitions refer to a physical state of being, specifically one without companions. Yet, in this digital age it's nearly impossible to be without companion. In fact, digital companions remove what I have always been told and believe are the least important aspects of good companions, specifically removing the physical appearance, sometimes granting new ones. We can be whomever we want online and talk to whomever we want, and yet, loneliness is just as important and prevalent as it has always been. I like your label for it “Networked Loneliness”. In some ways I feel like you answered your own question in posing it. What's so different today from 10 years ago is that networked loneliness didn't exist. We weren't networked.

In Data, you used simple wooden boxes to frame each artwork, and in Hit Counter you used a simple mechanical turn counter, instead of something more fancy. Why was that?

To be honest I'd have preferred an even simpler design. Had it been technically possible I'd have preferred a small wooden box, maybe the size of a plaque, instead of the large box I currently have.

The box is meant to emphasize the number. Hit Counter is a work that is very involved in its self. By making the box fancier it would add to the perceived value of the piece, and I'd prefer that the entire perceived value was derived from the number of people who have seen it. The simple counter is a reference to the style of web-counter that was prevalent in the mid to late nineties online.

Which artists currently working do you relate to most closely or draw inspiration from? Do you look at other fine artists in the near past, for instance, someone like On Kawara, Sol Lewitt, or, just off the top of my head, Dan Graham, and see yourself as "like" them?

This is a question I haven't thought about very much. I certainly love On Kawara and Sol Lewitt. I take a ton of inspiration from Sol Lewitt's “Sentences on Conceptual Art” in particular.

I think you actually picked the two artists I draw some of the most from although I wouldn't be so bold as to say my work is close to theirs.

On Kawara's work is so significant in that it is all objects, but conveys this heavy presence that has very little to do with the tangible artifacts themselves. I think I try and take a similar approach to that, looking to convey a heavy presence without the tangible artifact at all.

I've always wanted to make a parody shirt of On Kawara's work where I take the text of one of his paintings and put it on a t-shirt of the appropriate color. I think it would be a neat little jab at the commercialization of contemporary art.

How do you think of being present: what does that mean to you and how do you mean your work to ask people to think of that idea: presence and absence?

I think a lot of my work is a search for specifically that, a definition of being present in our digital age. To be so involved in a digital space but to never admit that we are there is so confusing and sad to me.

We certainly say we are there a lot. The tropes of existence and lack of it are all over the internet. "BRB" couldn't exist without a state of being 'here' and a state of being 'away', and yet, the way we treat the internet and one-another on it is still so much like it is a tool and not a place. We can only have a tool or not have one, a tool cannot 'have' or 'not have' us. But the internet does have us. To the extent that we exist outside of it, we also exist within it.

Joshua Noble is a designer, programmer, and author of several books on creative code, include Programming Interactivity. He's available at http://thefactoryfactory.com and on Twitter at @factoryfactory.