When introducing digital art to an unfamiliar audience, every piece becomes a manifesto of its own - it simultaneously informs, provokes and educates the viewer. When East London gallery SEVENTEEN put up "Intentional Computing", Paul B. Davis’ first ever solo show in 2007, this was precisely the challenge it faced. In Britain’s oddly conservative art scene, the show acted as a demonstration of the infinite possibilities and theorization of digital creativity. A brief retrospective of one of London’s most adventurous galleries brings out the problems such artists face as well as the complexities technology- savvy audiences are learning to incorporate into their viewing experience.

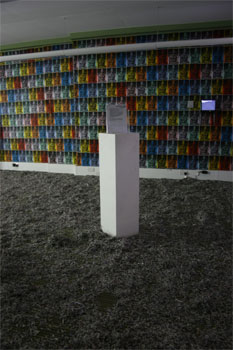

“Much of the work we began to show at SEVENTEEN was at first alien to people in London,” says Paul Pieroni, co-curator of SEVENTEEN, who had been a fan of Davis’ work with the collective, BEIGE, for years: “I liked the fact that it takes technology not on face value, but in terms of its place within a more diffuse contemporary culture.” "Intentional Computing" featured some of Davis’ NES hacks, as well as glitchy, pixelated videos, reminiscent of the artist’s early encounters with technology. It also raised debates about issues of commodity and reclamation. By quoting recurring parts of his technological environment past and present, including the computer games (Nintendo et al) of his youth, Davis was rejuvenating a practice innovated by major pop artists such as Eduardo Paolozzi’s work in the early 50s as well as his later mosaics, or Richard Hamilton’s famous collages.

“Paul’s work was both pop and highly theorized. I loved it,” Pieroni recalls, it also “left people scratching their heads.” SEVENTEEN went on to show more and more technology-based work, featuring the likes of John Michael Boling and Javier Morales, Eric Fensler, Charles Broskoski, Oliver Laric - as well as regular contributions by Paul B. Davis. “We’re definitely not a new media gallery”, Pieroni insists, “I don’t even like the term new media, it’s patronizing - to many people, there is nothing new about computers.” ‘Geeky gadgetry’ or rather, technology for the sake of technology, is not a sufficient artistic credo: rather, the gallery seeks artists who utilize digital tools-at-hand to make social critiques and talk about life, that is, “our lives in the era we might now call Civilization 2.0.” Technology is an undeniable force in today’s society, which is why SEVENTEEN’s new-media-based shows are never referred to as such: “It’s just art. We tried to avoid ghettoizing the work, and incorporate it with traditional media. It’s a matter of integration,” says Pieroni. On this quest to illuminate today’s tech-centric realities, every digitally-inclined show at SEVENTEEN seems to serve a slightly different purpose - covering new territory with each progressive show.

“We like what you eat” was the title of the gallery’s offering for Spring 2008. It served as a humorous investigation into the video-making practices of a number of North-American artists. This includes the aforementioned Paul B. Davis, Eric Fensler, John Michael Boling and Javier Morales. It presents a series of videos, highlighting the appropriation of mass entertainment media enabled by the glut of material available on the internet.

Like earlier video artists such as Robert Filliou, Steina and Woody Vasulka and even more so Nam June Paik, the ever-increasing presence of technology is tamed through the distortion and appropriation of the pre-existing mainstream. Yet while many of the earlier artists warned their audience against the power of technology, such as The Medium is the Medium (1969) or Filliou’s L’Esclave (1978) video, today’s stance shows a clear evolution. Moving away from a binary between screen and viewer, this generation embraces our highly technologized everyday; it utilizes distorted data to blur lines between art, technology, science - warped technology becomes a means of communicating, or rather allegorizing a societal critique. For example, Davis’ piece BYOBB (Bring your own Bobby Brown) juxtaposes current, glitchy video art with 80s DIY reference. It provides an unclassifiable piece of work that doesn’t single out a specific audience, and henceforth protests against the ostracization of new media art, or rather of any mode of creation as an insular category.

Fittingly, this show inaugurated SEVENTEEN’s newly converted basement space. This soon became a favored stage for various new media artist communities - an aspect of the art that had always appealed to Pieroni. “I like the fact that many of these guys are friends. It feels like a micro-movement. Like an old-fashioned art movement of ‘community’, only with everyone wearing day-glo shell-suits, living in warehouses called ‘ Camp Gay’ like some members of BEIGE in the early days and spending all their time online or fiddling with obsolete technology,” Pieroni states. The notion of a parallel, creative community, busy distorting the massive influx of information is a theme recurrent to the gallery. The group show "The Steve Guttenberg Galaxy" in Fall 2008, further maps out the digital movement: it featured once again the previous show’s Eric Fensler, Paul B. Davis, John Michael Boling and Javier Morales, but also included Berlin-based Oliver Laric, New Yorker Charles Broskoski, and British Richard John Jones. Through a self-derisory pun between the inventor of the printing press Johannes Gutenberg (1400-1468) and eighties actor Steve Guttenberg (b.1958), the show highlighted the ‘entertainment as culture’ we live in, whilst confirming the existence of a transnational, underground microcosm interfering with its means of transmission.

The presence of Oliver Laric the following month, with a show featuring three of his video works, 50 50 2008, ↓ ↑, and Touch My Body (Green Screen Version) presented a second generation of new media artists according to Pieroni, explaining, “Oliver feels like a child of BEIGE, that he is walking on the ground Cory Arcangel and Paul B. Davis laid out for him.” Touch My Body (Green Screen Version) eliminated everything in Mariah Carey’s music video except the chanteuse herself, replacing the background with a green screen. Once uploaded to the internet, users were able to freely remix the video, resulting in some curious and entertaining recycling of the original clip. This sort of crowd-sourcing aesthetic was also apparent in 50 50 2008, a bricolaged-sing-along video of anonymous people chanting to one of 50 Cents’ hits. Laric perfects a technique that had been drafted by his predecessors: “This is a kind of YouTube modernism, dedicated to refining a specific idea or medium to its ultimate point” explains Pieroni. By using two identifiable pop references, it addresses itself to a new audience acclimated to a YouTube interface, and thus highlights the rapidly evolving, ephemeral nature of new media art. The immediate accessibility the site provides allows an unprecedented amalgam of content - from mainstream pop to obscure references - and is a product of Laric’s generation more than Davis’. This infinite database, evenly formatted to a short clip format, disrupts a cultural hierarchy and thus blurs lines between audience groups.

This theme of temporality is further explored in the show "Define your terms (or Kanye West fucked up my show)", Paul B. Davis’ second show at SEVENTEEN. There, the artist acknowledges a forced evolution, after seeing mainstream rapper Kanye West’s latest video, using similar pixilated effects -which Davis had planned on using in his upcoming show. This, to quote the artist, had indeed fucked up his intended show. This moment of truth represents the quintessential Derridean realization, that one is never able to escape the system one seeks to criticize. Therein lies the double bind that traps new media artists and forces them to continuously question what they are doing. “The very language I was using to critique pop content from the outside was now itself a mainstream cultural reference,” Davis commented at that time. This seemingly difficult situation is, it could be argued, the condition for reflection and renewal. And there is more. Beyond the obviously technologically-involved shows, SEVENTEEN promotes an approach to curation informed by new media practices. Take, for example the show "We would like to thank the curators who wish to remain anonymous" from April 2008. Here curatorial practice is presented as a performance in itself, as presentation is as important as the art works that are shown, something that is frequently forgotten in museum shows but that the gallery wanted to highlight. Furthermore, the title might be an immediate reference to the internet’s debates over anonymity and authorship.

In other words, these references highlight the fact that the internet imposes rules and affects basic norms that inevitably trickle into every day life. “Call it the googlification of everything,” says Pieroni. “We are not consciously reproducing or challenging forms of viewing,” he says, “it just happens that during the Noughties, the internet has served as the catalyst for a massive shift in the way we do everything.” By operating within a non-new-media specific framework, SEVENTEEN is contributing to the acceptance of new technologies within the art world, by larger audiences. As Pieroni put it “The internet is a speculative opportunity. I like artists who exploit this opportunity.”

Alice Pfeiffer is a writer interested in artful matters and the future in general. Pfeiffer graduated last year from the London School of Economics with a Masters in Gender and Media Studies. She writes for the global edition of the New York Times, and she is a contributor to Interview and Dazed and Confused. Prior to this, she worked as an editorial assistant for Paperback, and wrote food reviews for Time Out UK. She generally likes anything involving robots or pastries.